March 1853

“The frost appears to be gradually departing, and we may hope for a little fine open weather [so as to] prepare the ground and get in the spring crops. Planting operations should also be carried out vigorously.” So reported the Bell’s Weekly Messenger at the close of February

Come March, so it was. Spring was showing signs of having arrived. The seasonal rhythm of the year was beginning to make its mark, agricultural activity now getting underway.

Good progress was being made with livestock; the young lambs were showing and calving was almost all done. The ploughs were now out in the early fields. The frost and then the rain during February had meant delay but now the smell of slurry was becoming prominent across the eighteen farms in the parish.

In the fields set aside for hops, the priority was weeding, followed by the set of the hop poles which had been bought during the start of the year. Some poles were as much as twelve feet high, the wires for the bines hung between. Only then could a start be made sowing of the famous Farnham White Bine. As ever, farmers held hope in the prospect of reward for investing in those premium hops. They would be picked at time of harvest both by local workers and by the Romany and other travellers who came into the area during late summer.

With birds in full song in the trees and hedgerows, it is not too fanciful to believe that the village had taken on a general mood of optimism.

Adding to the sense of change in the village, the Reverend Henry Carey was now in his last few weeks of his tenure, perhaps in reflective mood. His diary informed him of some important dates. The curate’s last meeting with the Vestry would be held at the parish church; it was fixed in his diary for the 23rd. More immediately, he had three christenings to perform at Matins on that first Sunday. He was also to read the banns for two weddings which were marked in for the 14th.

Happily, the curate’s diary would be free all month of notice of upcoming funerals. Had he opted to inspect the burial register and paused to do the sums, Reverend Carey could calculate a rate of just over one per month since October 1838, based on a total 177 burials during the 174 months of his tenure. However, on a less melancholy note, were he to include the three christenings noted in his diary, the curate could count 366 baptisms during that same period. With over twice as many baptisms as burials, simple calculation indicated that he had seen growth in the population of the village, although with the numbers leaving the parish being greater than had the arrival of newcomers.

Of course, there had been many newcomers; he and his wife had been that too, from Guernsey. Most others though had been from the nearby counties, or from London. The voices he had heard varied but all but a few were recognisably English. Indeed, perhaps only the Mackenzie and Finch family stood out.

Henry Mackenzie was, as his name implied, from Scotland. his two teenage daughters also born in Scotland. His wife was English, and the birth of their son William had been registered in Farnham in 1846. Until recently he had been farming 30 acres at the Moors at the top of North Lane, on land owned by John Saunders. Saunders had died in 1851, aged 81, and left his estate to his sister-in-law Mary Searle, who was also elderly and died shortly after. By 1853, Henry Mackenzie and his family had left the parish, the land now farmed by George Turner, sale of ownership under negotiation with the George Trimmer, the auctioneer and farmer from Farnham who was not yet turned 30.

Ann Finch was from Ireland. She was the wife of George Finch, another of the Chelsea Pensioners living in the village. He of course was from the area, born and baptised in Farnborough. At the age of 20, he had enlisted in Farnham with the 41st Regiment of Foot in 1826, ten years after Waterloo. Rising to the rank of sergeant, he was a veteran of the first Anglo/Afghan War which had been waged in an attempt to protect the interests of the East India Company from Russian incursion.

Both his wife and their son Emmanuel were born in Ireland: Ann was born in the County of Kilkenny and was most likely Roman Catholic, Emmanuel in the County of Kerry, where Ann and George were when he was stationed there in 1837 with the 14st. Whether both spoke with an Irish accent is uncertain, sons of soldiers often acquiring a mixed brogue during childhood. Emmanuel was aged 16 by 1853, listed in the Census two years earlier as an agricultural labourer.

Reverend Carey would certainly have noted that the date of Easter would come early this year. Indeed, there was a complication: Good Friday would fall on the 25th, the same day as the Feast of the Annunciation, one of the ‘immovable feasts’ in the Church calendar. Marking nine months before Christmas Day and the birth of Jesus, the celebration would coincide with the ceremony devoted to his crucifixion.

Clearly marked in the diary was Easter Sunday on the 27th. The tradition, laid down in the Book of Common Prayer from 1552 onwards, was that,

“yearly at Easter, every parishioner shall reckon with his parson, vicar or curate … and pay to … him all ecclesiastical duties, accustomably due …”.

A good turnout by the parishioners at St Michael’s Church would make for a fine end to his tenure of fifteen years as curate, and perhaps a sizeable Easter Offering.

5th March 1853

According to the Hampshire Chronicle, Captain Higginson of the Grenadier Guards had been engaged for several days taking a survey of Ascot Heath. His purpose was to select a suitable location for the encampment of 7,000 troops during May and June. Surveys had also been made of Windsor Great Park, Hounslow and the Bagshot Heath. The plan was to encamp as many regiments there at the same time as could be spared. The reportage of that was on the second page might easily have been overlooked, buried towards the bottom of the last column.

The presence of soldiers on horseback on Aldershot Heath during those several days past might also have passed unremarked. Unreported by the press, however, was more specific information about planning within the military. Higginson’s senior officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton, had been ordered to look at the country south of Farnborough and extending across the canal to a village called Aldershot.

Report of the death of Sir Edward Doughty at age 71 also featured in the Hampshire Chronicle and in the London Evening Standard. He was the 8th holder of the Tichborne baronetcy, the son of Sir Henry Tichborne, the 6th baronet. Before unexpectedly succeeding to the Tichborne title from his older brother, Sir Edward had changed his name to Doughty in order to qualify for a large bequest.

Tichborne and White

The marble monuments that adorned the wall of St Michael’s Church would have been eager to remind Reverend Carey of the significance of the Tichborne family.

The Tichborne family claimed to be able to trace their family tree and significance back to Anglo-Saxon nobility. They were staunch Catholics, remaining recusant at the Reformation. Tolerated during Elizabeth’s reign, Sir Benjamin Tichborne was the High Sheriff of Hampshire who had arranged the swift coronation of James I & VI at Winchester as heir to Elizabeth. The family thereby secured favour and protection from the Stuart kings.

The marriage of the two sons of Sir Benjamin, Richard and Walter, to the two surviving daughters of Sir Robert White, ensured that Tichborne family would feature in Aldershot’s history, as was very evident in the memorials to various personages in brass and marble with St Michael’s Church.

Taken together, those memorials reflected mixed fortunes during the three hundred years since the Protestant Reformation in England, having a strong Catholic undercurrent with which Reverend Carey was surely aware.

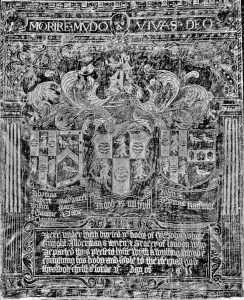

Chief amongst those memorials was that for Sir John White on a brass plate of his own design.

As curate, Reverend Carey would doubtless have known that this memorial was adorned with the insignia of the City of London, the Merchant Adventurers and the Grocers Company. Sir John had been a successful international merchant who rose to become Lord Mayor of London. At his request, he was buried in Aldershot in 1573.

What Reverend Carey would most probably have learnt during his fifteen years was that this man was called John the Younger, one of two brothers called John White. The other, John the Elder, had been the last Catholic Bishop of Winchester, predeceasing his brother in 1560. There are many twists and turns in the lives of the two brothers.

The brothers were born in Farnham between 1509 and 1511, descendants from a merchant family with influence all across the south of England, the significance of which begins locally with Robert White of Yateley. The brothers were the third and fourth sons of another Robert White, part of the junior branch of the family. An elder brother, another Robert, took over the family business in Farnham at their father’s death in 1518 until his own death in 1534. The second son Henry had a scholastic career, becoming Principal of the Canon Law School at Oxford. It is through Henry’s will that it is possible to distinguish which was the elder and younger of the sons named John.

-

- The will of John’s elder brother Henry states that “Brother John White [elsewhere “John White the yonger”] Grocer of London” is “to have peacible possession of testator’s Londes in Aldershot”. The statement by Father Etienne Robo (‘John White: Two Brothers’ written in 1939) that he was the elder of the two brothers called John is erroneous, a mistake which is sometimes repeated using Robbo as authority.

Sir John died aged about 63 years old. He put the place on the map, although with spelling of the place as ‘Aldershare’, as displayed in a map of Hampshire made by Christopher Saxton in 1575, part of the ‘Atlas of England and Wales’ published in 1579.

From a digitized copy of a map in collection of Hampshire County Council Museums Service (item number: HMCMS:KD1996.1).

There were also brass plates in St Michael’s Church for Sir John’s son Robert and his wife Mary. His son had added to the considerable freehold and copyhold estate his father had amassed in Aldershot, Tongham, Frimley and elsewhere.

When Sir Robert died in 1599, his estate passed to his two surviving children, both daughters, this inheritance along the female line enabled under the custom of the Crondall Hundred. Ellen and Mary later married to two sons of Sir Benjamin Tichborne. Their deaths were also the subject of marble memorials. One on the north wall was of a female figure knelt in prayer below which was written,

Erected by Sir Richaed Tichborne, Knight,

to ye memory of his dearest wiefe

the Lady ELLEN TICHBORNE,

eldest daughter of Robert White, of Aldershott, Esq.

who godly departed thys lyfe the 18 day of May,

in the year of our redemption 1696, and of her age 27.

The other was of a female kneeling with seven sons and six daughters,

Here lieth ye body of Lady MARY TICHBORNE,

ye wife of Sir Walter Tichborne, Knight,

who was married to him ye 7 of May 1597,

and deceased ye 31st January 1620,

leaving issue, now living.

When Richard’s wife Ellen died, the White estate then passed to Mary, the wife of his younger brother Walter. Her descendants then inherited, meaning that it was the junior life of Sir Walter which became established at the freehold property of Aldershot Park [* edited, see below], also having properties across Aldershot and in Cove and Frimley.

Sir Richard, the elder of the two sons, succeeded to the title in 1629 and moved to Tichborne Park. [** edited, see below]

The Tichborne descendants supported the Stuart King Charles in the Civil War. The family were to find themselves increasingly on the wrong side of history, especially from 1689 onwards. With various twists and turns, the importance and then presence of the Tichborne family in Aldershot diminished, their properties all sold off, two of the three mansions demolished.

6th March 1853

The fine weather made Mothering Sunday seem like a Spring festival. It was also the only day that domestic servants could expect a holiday, based on the tradition of sons and daughters of the parish returning to visit their parents.

Three christenings took place at Matins.

Charles Young

The first entry in the baptismal register that day was the third child of Martha and her husband, also called Charles. They had married at the same church in March 1847, their first child together also baptised at the parish church in June 1848 and their second in 1851.

The infant child Charles was the fifth known to be born to Martha. Born in 1818, as Martha Matthews, she had left home by 1841; likely, she was then another from the village living in Islington, a servant, with the same name and aged 23, at St Paul Place. Martha was back in the area in the second quarter of 1844 to register the birth of her daughter ‘Miriam Crane’ in Farnham. Her son Richard was baptised in Aldershot in 1846, also recorded as illegitimate.

At the time of the 1851 Census, Martha had four children, two listed under her maiden name of Matthews. She was recorded as a Martha Young, as ‘wife’, but she was living on her own at the far end of North Lane, listed as a seamstress. Her husband Charles Young was listed as spending Census Night in the cells at the Police Station in Farnham. (No newspaper reports of a subsequent criminal trial are found: perhaps, he was wrongly arrested or just given a night in the cells after a Saturday night in the local market town.)

Esther Barnett

Also baptised that day was Esther, the daughter and third child of John and Ann Barnett. There were very many called Barnett in the village in 1851, five were named John. Esther’s father was the John Barnett who had married Ann Hudson from Yorkshire. She had been born in Bishop Monkton, near Harrogate.

Their eldest child, also called John, had been baptised in January 1849 in a place called Haughton in Staffordshire. This was over 130 miles away from Aldershot. However, Haughton was only six miles from the market town of Penkridge from which John Shaw had arrived in the mid-1840s with his wife Mary, daughter of the late Mary Hughes.

John Barnett was the son of Stephen and Martha Barnett and therefore the brother of Caroline, now Mrs. James Elstone. Likely all would have been gathered around the font.

Reverend Carey would have recalled that he had baptised John and Ann’s second child Henry privately on 14th February 1851, a second public baptism also recorded at the Church of St Michael in March of that year. Such a double baptism occurred when there was fear of the death of an infant near to birth.

William Attfield

This child was the son of another agricultural labourer, also called William Attfield. He had moved into the parish in recent years, staying next to George Gosden, the grocer. The name of the child’s mother was Caroline, but, perhaps having been distracted, the Reverend Carey mistakenly recorded her name in the baptismal register that day as Mary.

The parents were both baptised in 1822, William in July and Caroline in January, at St Andrew’s Church in Farnham, which was where they later married in March 1841. In June, the Census listed William at Hoghatch in Upper Hale, staying with his older brother John and his family.

The first of their children was born in 1846, baptised in Aldershot, an indicator of when he and his wife might have initially moved into the village. William’s brother James, who had also married another daughter of an agricultural labourer from Folly Farm in Hale, had been the first to move into the village, his child baptised at St Michael’s Church in 1842. (That was the year in which St John’s Church at Hale was first opened.)

William and James were nephews of George and ‘Nimmy’ Attfield. Thomas Attfield the Parish Clerk was therefore a cousin.

10th March 1853

Change was also happening up at what was locally referred to as ‘the Union School’. This followed a visit in the previous month made by a Committee of Directors and Guardians of the Workhouse at Brighton in Sussex. The visitors expressed favourable comments on what they called the ‘Industrial School’ at Aldershot and on the advantages and benefits of an improved system of separate provision for minors.

The school was under the control of the Board of Management of the Farnham and Hartley Wintney School District. The Board had now wished to make new appointments, namely a new Superintendent and a Matron. On offer was the combined salary of £70 per annum plus supply of rations and apartments.

The Board of Management may have had other reasons for upgrading the post from supervisor to superintendent. Indeed, the route that Francis Henning had taken to the post of supervisor gives no indication that he had any training as a schoolmaster. He had been recorded as ‘Master of the Aldershot Workhouse’ in the register for the baptisms of his first and second child, in December 1847 and February 1849, respectively. Before that, he had been the porter and baker at the Alresford Union Workhouse in 1841.

The Board’s decision might also have been associated with the recent trauma experienced by the previous supervisor. Francis Henning and his wife had suffered the death of their infant son at the beginning of February. The child, their fourth, had been only eight weeks old.

-

- Correction: The family were in Aldershot in 1861, staying on Drury Lane, Francis was listed as a baker.

The curate was familiar with the history of the building used for the District School. It had previously been the Aldershot Workhouse. The Census records its use in 1841. The Vestry had favoured providing poor relief to families in their home, so-called ‘outdoor relief’, and had subsequently opted to use the Farnham Workhouse only for the few that required indoor provision. The workhouse building was later sold to the Farnham Poor Law Union.

Plans for its use of the building for the children of the Union were drawn up by the Guardians of the Farnham Union in 1846; in May they had invited plans for alterations to the building for that use, stating that they would pay 10 guineas for ‘the most approved plan’. In October that year, the Farnham Union placed an advertisement for a school master and schoolmistress, also to act as Master and Matron, with salaries of £20 and £15 per annum plus rations . That policy subsequently altered and the building later opened as a District School for three Poor Law Unions in 1850..

What was probably also known by Reverend Carey was that the Aldershot Workhouse had itself been rebuilt using materials from a demolished mansion.

=> More about the Aldershot Workhouse will be said in the (later) chapter May.

14th March 1853

There were two weddings on that Monday. Esther Hughes would not have been alone in noting that the two brides were with child. Her niece Jane Fludder was to marry Moses Matthews; Eliza Hall was to marry Francis Newell. The couples acted as witnesses for one another. All except Eliza would sign their names in the register; she alone had to make her mark.

The first bride, Jane Fludder

This wedding was altogether a much happier gathering for the Fludder family, young Frederick’s funeral still strong a memory. Jane’s Aunt Esther would perhaps have been concerned whether her younger sister, Jane’s Aunt Mary, would attend the wedding at the Church so soon afterwards.

Jane and Frederick had been cousins, both children of single parents who spent their early years in their grandparents’ home at the outskirts of the village, both then subsequently to be under the charge of a stepfather.

Jane was now aged 25. Not only expecting but already a mother, her three year old child born in Farnborough and baptised at St Peter’s Church in Ash. Jane had then moved back to Aldershot with her infant daughter Lucy to join the household of her mother’s older brothers John and William Fludder. The two uncles were both widowed, her Uncle John having had to raise two young sons, now aged 14 and 16.

Jane’s mother Eleanor had also been a 22-year old single mother when Jane was born. The parish baptismal register recorded Jane as “Illegitimate of Ash”, James Robinson noted as the father. There were many with the name of James Robinson in the general vicinity. One credible candidate was the son of James the cordwainer (b. 1768) from Shawfields, in Ash, just over the County border from Deadbrooks, quite close to the Fludder homestead.

When Jane was eight years old, her mother married the widower Henry Wareham [‘Warsham’], at Windlesham in December 1837. He was listed as a publican, his residence given as Bagshot. Jane’s mother Eleanor was listed as a housekeeper. Henry was able to sign his name; Eleanor had to made her mark instead. Eleanor’s father, George Fludder, Jane’s grandfather, was listed as having been a butcher; he would then have been in his late 70s at the time.

By the age of twelve Jane was part of a blended family at the Kings Head, Frimley, in 1841. She was with two others of similar age having the same name as her stepfather, presumably a son and daughter by a previous marriage, as well as two infants of the new marriage, Sarah and Henry. Another child was baptised in Frimley the next year in July 1842; Jane’s stepfather was again listed as a publican. By 1851 Jane’s mother Eleanor had moved with her new family to Fish Ponds in Farnborough. Jane was not then with them but, as stated, he was in Aldershot in her uncle’s household.

Moses Matthews, Groom’s side

Moses was a carpenter as had his father been. Born in 1823, he was older than Jane by almost five years. Moses was from a large family. He was the eighth of at least ten children born to Stephen and Ann Matthews.

Esther Hughes might have mused how she had herself married a sawyer from a large family. However, she knew Moses’ family history to be much more tragic and troubled than that of her George. In addition to the death of both parents, Moses had experienced the loss of a sister and four brothers during his childhood.

Moses had been raised on Place Hill, the lower road to Farnham which ran up from near the Ash Bridge towards Badshot Lea. He was there in 1841 with his parents, his older brother James, also a carpenter, and three other children with the name Matthews. By then the eldest of the Moses’ brothers and sisters had left home.

Moses’ parents, Stephen and Ann, had to endure the deaths of several of their children. Their daughter Maria, a year older than Moses, was buried aged 13 in February 1835. Moses’ little brother Mark also died that year, in August, aged only six.

Then came the deaths of Moses’ two older brothers. John died of ‘consumption’; his death was registered in Ash, the Reverend Carey conducting his funeral at St Michael’s Church in September 1839. Within two years the other brother, James, died of ‘pulmonary consumption’ at age 25, buried in July 1842. With the death of James and John, the household lost the income of breadwinners as well as close kin.

Moses’ brother Stephen, the eldest in the family, had been baptised as long ago as 1808. He had left to marry Mary Lee in Seale in 1829. They had a son called Thomas, baptised there in July 1830, and later a daughter, baptised as Jane in Aldershot in January 1832. In 1841, they were both placed with relatives. Thomas was with his grandparents, Stephen and Ann, at Place Hill; Jane was with Mary’s sister and brother-in-law Henry Deadman at Normandy Green. The later fate of Moses’ brother Stephen and his family is unclear, but perhaps he was working elsewhere.

It seems probable that Fanny, the eldest sister in the family (bap. 1809), had entered domestic service somewhere during the 1820s. Another of Moses’ sisters called Emma had left: by 1841, she was one of two female domestic servants for Mr John Eggar at the Manor House. She later married when she was aged over 30, to Christopher Brown in 1845. Moses’ sister Martha had also left home, also for domestic service. She had two children prior to her marriage to Charles Young. Their son had been baptised earlier in the month, on March 6th.

The youngest in the household at Place Hill in 1841 had been Matthew Matthews, listed by the June Census as aged 4. The parish register lists his baptism in May 1838, another noted as ‘baseborn’. His father is recorded as William Mason who was a local potter aged 24. His mother is recorded as Ann Matthews, but this is a puzzle. Moses’ mother Ann Matthews had been aged 23 years old when her firstborn was christened at St Michael’s in August 1808. Thirty years later she was aged 53, an unlikely age to give birth. What seems more likely is that the Matthew was the child of one of her daughters, although which one is unknown; none is recorded with the name of Ann; perhaps that might have been a name used within the family.

By 1851, none of the Matthews family were living at what had been the family home on Place Hill. Moses’ mother Ann had passed away in 1843 at the age of 62, His father Stephen buried in November 1849. Moses’ sisters Mary and Jane were in London in 1851 as visitors to the household of a family called Brown; they might have been related in some way to the husband of their older sister Emma who had married Christopher Brown six years before. Matthew Matthews, the youngest in the family, was enrolled at the ‘Union School’, the only pupil at the school born in Aldershot.

Moses himself had been lodging at the Beehive Inn as a carpenter in 1851. Despite an early life full of family tragedy, he now stood, aged 30, at the front of St Michael’s Church. He and Jane Fludder, very soon to start a new family of their own.

The second bride, Eliza Hall

Eliza was also soon to be a mother, the child later to be baptised at St Michael’s Church as she had been 17 years before. Eliza was the daughter of John Cawood and Mary Hall, each widowed, and living as man and wife with children from those previous marriages.

Mary had married a man called Henry Hall. Curiously, John Cawood had married another woman called Hall in 1823, Maria being aged 13 and wed with the consent of her parents, William and Mary. She was baptised in Farnham, in 1809, as was a Henry Hall earlier baptised in 1797, the son of John and Mary. Eliza’s parents, Mary Hall and John Cawood, might, therefore, have been widowed to half siblings.

In any event, it was complex.

Eliza’s parents household in 1841 included her mother Mary Hall, together with her older children, George (bap. 1822, Aldershot), Henry, William and Stephen. these all having the name Hall. Eliza and her younger brother Charles were then recorded then as Cawood, after her father John Cawood, together with his daughter Caroline from that earlier marriage, baptised in January 1826.

The household was much the same in 1851, except that her mother had died and her father’s older daughter had left. Eliza and her younger brother Charles were now recorded with the surname Hall, Eliza being listed as a lodger and house servant. Eliza’s half-brothers Stephen, George and his wife Ann all had the surname of Hall, all listed as agricultural labourers.

(Cawood was a long-established family name in Aldershot, several being baptised at St Michael’s Church, more than one called John.)

The Groom, Francis Newell

Francis’ family background was not as complex. He was a sawyer, baptised locally in 1828. He was the son of James Newell, another locally born sawyer . His mother Mary was the daughter of the farmer Robert Lloyd.

Francis was one of six children, his younger siblings born in Godalming which was where the family were in 1841. They had moved back to Aldershot by 1851, located by the Manor House. It is unclear where Francis was then living. However, Francis and Eliza would stay on in Aldershot after their marriage, Francis continuing to work as a sawyer.

His older brother James was in their father’s household in 1841. He moved out the next year and also set up as a sawyer in Aldershot, his wife, from Egham. They were on North Lane in 1851 with five children aged under 10, all born in Aldershot.

-

- (There was another in the village called Francis Newell of similar age who was recorded by the 1851 Census as an an agricultural labourer lodging at the Red Lion Inn. He had been baptised in 1826, the son of Thomas, an agricultural labourer. That Francis Newell married in Shoreditch to Jane Stonard in 1852. She was the daughter of the brick burner William Stonard, and was in her father’s household in 1851, listed as a lady’s corset maker. The couple later settled in St Luke’s, Finsbury in London, that Francis Newell becoming a leather cutter.)

15th March 1853

The funeral of Sir Edward Doughty, the 8th Tichborne baronet, was a grand affair, taking place ten days after his death. It was held at the family chapel at Tichborne Park at noon, officiated by the Catholic Bishop of Southwark and assisted by as many as 14 priests. There were reports in various regional newspapers, the fullest terms in the Tablet.

23rd March 1853

Much of parish administration was conducted by members of the Vestry. It met at the Church that Wednesday. Their remit included the relief of the poor in the parish as well as the state of road and highways.

In earlier years the Reverend Carey chaired Vestry but recently that had been carried out by the laity. Charles Barron Esq was in the chair that Wednesday. Others members attending Vestry included Richard Allden, James Elstone, Captain Newcome, Henry Twynam, William Herrett, Robert Hart, George Gosden and Richard Stovold.

These were the men of influence within the parish, mostly landowners but also admitting some significant others who were rate-paying residents. Conversely, the Vestry did not have all the landowning families represented, only those who were resident in the village. The holdings of the Eggar family had been leased to the tenant farmer Henry Twynam.

The main item of business for the Vestry that evening was to confirm who would serve as the parochial officers for the year following, although much of that might already have been informally decided. The changeover would take place two days later, on Lady Day, March 25th.

The Chairman of the Vestry for the next year would be George Newcome, a retired Army Captain who had bought the Manor House estate in 1847. He would also serve as one of the two churchwardens alongside Charles Barron, the land proprietor from London who had owned the Aldershot Place estate since 1828. Barron would serve for a second year, Reuben Attfield would be stepping down from that role, although he would continue in several others.

The main civic office was that of the two Overseers, voluntary positions with responsibility for levying the rates and for the administration of various charitable funds. The two nominated to serve as Overseers for the next year were the farmer James Elstone of Aldershot Lodge and John Thomas Deacon, the retired gent from London who lived at Ash Bridge House.

Looking back over the Vestry minutes, the curate could note the five families prominent in the role, generally with full turnover each year:

-

- Attfield: Reuben 1834, 1841, 1847 & 1852 (first when aged 32)

- Allden: James 1833; Richard 1838 & 1845 (first when 45)

- Elstone: James Snr 1835 (aged 68); James Jnr 1842 & 1854 (first when 37)

- Eggar: John [Senior] 1833 & 1840; Eggar, John [Junior] 1847

- Robinson: George Snr 1834 & 1835; James 1837; Robert 1839; George Jnr 1842, 1843 & 1845

There had been a widening of the selection in recent years, the Vestry no longer just the preserve of the landowning yeoman farmers. Office holders now included tenant farmers and gentlemen who had retired to the village. Locally born William Faggetter was a tenant farmer who had moved back into the village to take over the operation of West End Farm. Francis Deakins Esq was from London, described in the 1851 Census as a retired gardener. Both were stepping down from the role of Overseer having served for a year. In a previous year, William Fricker, another from London, had shared the role with Reuben Attfield.

Neither of the occupiers of the role of Overseer was paid for the duties performed. Instead, the Vestry supported them in their duties with the paid position of Assistant Overseer. For many years that role had been undertaken by the farmer Thomas Smith. However, in 1852 the Vestry had agreed that the ever-willing Reuben Attfield should undertake that function, on an annual salary of £20. This followed the presentation to him in the previous year of a silver cup bearing the inscription,

“A tribute of respect from the parishioners of Aldershot

to Mr. Reuben Attfield

for his voluntary and very useful services in the affairs of the parish.

Presented in the year of the Great Exhibition, 1851.”

His salaried appointment as Assistant Overseer in 1853 coincided with the sale of Parkhouse Farm and his other properties in the parish.

Reuben Attfield undertook also the role of Collector of Taxes, responsible for the collection of the thrice-yearly Poor Rate and the annual Church Rate. He shared that task with the tenant farmer Henry Twynam. They replaced the farmer Thomas Smith and William Downs, a dealer resident in the village.

Other senior positions elected by the Vestry included the Surveyor of the Highways, filled by Richard Allden. The other was that of the Guardians on the Board of the Farnham Poor Law Union. They had a dual function, to represent the interests of the poor and needy and also to represent the ratepayers in the provision for those who were poor and needy. Two stalwarts, Richard Allden and James Elstone, were nominated to manage the ambiguity of the role. At this time formal responsibility was with the Board of Guardians of the Farnham Poor Union. However, the Vestry had retained an active policy of helping ‘out of doors’ including the provision of paid work.

There were then roles to be performed by individuals of lesser social standing. Henry Elkins the baker was to continue as the Parochial Constable for the year, appointed at a salary of £1 for the year. Joseph Miles, a man of many parts, would remain as hayward, charged with ensuring that there were no infringements of parish and common land and that hedges were maintained.

25th March 1853

Named generally as Lady Day, the date of the Feast of the Annunciation was immovable, fixed in the Christian Calendar at nine months before the birth of Jesus on Christmas Day.

Historically, as the first of the Quarter Days – the others being Midsummer Day (24 June), Michaelmas (29 September) and Christmas Day – it defined the agricultural and business calendar as well as having spiritual significance. It marked both the end of the financial year and the start of the growing season.

Despite the changes brought about by the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1752, which had shifted the financial year to April 5th, Lady Day remained the traditional day on which year-long contracts took effect for master and servant and between landowners and tenant farmers. It was also the date of entry for newly acquired fields and farms.

Knowing that the date therefore was an occasion which had a combined sense of agricultural as well as spiritual renewal, Reverend Carey would want to find words suitable for his sermon for the service on Lady Day. Curates generally turned to the Book of Luke for both the reading and the basis for sermons at the Feast of the Annunciation.

Verses 26 to 38 in the first chapter of Luke describe how the Angel Gabriel made known to a virgin she would conceive a son to be called Jesus. Although recognised by the Anglican Church, these verses were the cause of doctrinal difference between the Protestant Faith and Catholic Church of Rome, the latter making specific reference to Our Lady Mary the Virgin and placing emphasis on the significance of ‘immaculate conception’.

There was an added complication: in 1853, Good Friday also fell on the March 25th, the same date as Lady Day. The reasons for this clash lay in the way in which Easter, a ‘moveable feast’, was determined. Rather oddly, the date of Easter, arguably the most important date in the Christian calendar, was still based on calculus important to the pagan, namely the phases of the moon in relation to the vernal equinox, that moment when the day and night are of equal length.

The challenge of selecting words and determining liturgy suitable for both the suffering on the Cross and the joy in the Annunciation was a dilemma, one which had occurred before during Reverend Carey’s ministry, in 1842.

Matthew Bridges

This might have prompted Reverend Carey to have disturbing memories of Matthew Bridges, the hymnist who lived in the village from 1842 to 1847. His stay in the village had coincided with the growing influence of John Henry Newman.

Lady Day in 1842 marked the entry date for Matthew Bridges to take up possession of the Manor House estate, bought from John Eggar in that year. Bridges was a well-known poet and writer of hymns. His ‘Romish beliefs’ towards the Blessed Mary the Virgin were very much at odds with the teaching of the Evangelical wing of the Church of England. That was led by Bishop Charles Sumner, his palace at nearby Farnham.

Matthew Bridges brought with him a conflicted background of belief, illustrative of the cross-currents then prevalent in religious matters. He had been baptised and raised within a family committed to the Church of England; his two older brothers had been ordained. One was the Reverend Charles Bridges, an Evangelical whose books were widely read; The Christian Ministry was published in as many as eight editions in twenty years. Matthew Bridges’ wife Sarah, ten years older than himself, had been baptised in 1789 in a non-conformist chapel in Bristol, which later became a centre for Primitive Methodism.

Sarah was the daughter of Dorothea and Samuel Tripp, a lawyer’s son from Somerset who moved to Bristol and had made a fortune there as a manufacturer of soap. Her older brother became a minister in the Unitarian Church.

Bridges had subsequently come under the sway of the Reverend John Henry Newman, an ordained priest within the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church of England. Known as the ‘Oxford Movement’, this was a ‘high church’ group which argued for the adoption of Roman Catholic doctrines and liturgy associated with the Church before the English Reformation.

During his time in Aldershot, Matthew Bridges’ daughter converted to the Roman Catholic Church. That event in 1845 was announced in The Tablet, a newspaper launched five years before to promote Catholicism in Britain. Other newspapers and magazines carried the story, nationally and abroad. In the same year the Roman Catholic Church admitted John Henry Newman; he travelled to Rome the next year to be ordained by the Pope as a priest.

The Tablet was clearly interested in highlighting the probable stance of ‘Matthew Bridges Esq’ who himself became a Catholic in 1848, a year after he sold the Manor House estate to Captain Newcome. Bridges’ last recorded attendance was at the meeting of the Vestry Committee in January 1845. He was not recorded in the minutes thereafter.

Matthew Bridges would later publish ‘Hymns of the Heart for the Use of Catholics’ in 1848 and the more famous hymn, ‘Crown Him with Many Crowns’ in 1851. However, that latter hymn contained references to the Virgin Mary and was unacceptable to Protestant doctrine. The Anglican clergyman Godfrey Thring would later release a version which was suitable for singing in Protestant churches, removing those references to the Virgin.

The Tichborne Dole

Just when the Reverend Carey, a man from Guernsey, would first have heard about the tradition of the annual gift (or dole) to the poor of bread at Tichborne Park is not known. Perhaps it had been told him by his parish clerk Thomas Attfield, embellished with the story of Lady Mabella’s Curse which foretold that the name of Tichborne would die.

The story had its origins in the 12th Century when Lady Mabella was the good wife of Sir Roger Tichborne, a soldier in the service of Henry II. She extracted a promise from him on her deathbed that on each Lady Day he would give a gift (or dole of flour) to the poor of the manor. Lady Mabella warned that were this annual gifting ever to be abandoned by any of his descendants, then the name of Tichborne would come to an end. She said that this would occur when a generation of seven sons was followed by one of seven daughters.

The practice of the Dole did continue for many generations at Tichborne Park by the descendants of Sir Roger. That included Sir Benjamin who had been granted a baronetcy by James I & V and his eldest son, Sir Richard Tichborne.

It so happened that, in 1748, the baronetcy and Tichborne estates passed from the senior line of Sir Richard to that of the younger son, Sir Walter which had first settled in Aldershot. By the time of this transfer, the locus of that junior line had shift to Frimley, away from Aldershot where their copyhold lands had been sold.

On succeeding to the title, Henry Tichborne of Frimley became the 6th baronet, moving to the family seat at Tichborne Park, the freehold property at Aldershot Park being allowed to fall into ruin. His son, another Tichborne named Henry became the 7th baronet at the death of his father in 1785, later selling the family estate of Frimley Manor in 1789.

The 7th baronet, Sir Henry, who did indeed have seven sons (Henry, Benjamin, Edward, James, John, George and Roger), was the man who ended the Tichborne Dole in 1796.

More than that, Henry Joseph Tichborne (b. 1779), on becoming the 8th baronet in 1821, did have seven daughters Elizabeth, Frances, Julia, Mary, Catherine, Emily and Lucy. Athis death, at age 80, he had no living sons from his marriage.

All was therefore had come to pass according to the Lady Marbella’s Curse, as set out within stanzas of the ‘Tichborne Dole’ published in the 1830 edition of Marshall’s Pocket Book. This told of her prophesy about the extinction of the male heirs, paying handsome compliment to the female descendants of the family.

When Sir Henry Joseph died in 1845, without a male heir, the title passed to the eldest of the surviving brothers. This was Edward, as Benjamin, the second eldest, had already died, in China in 1810.

As though true to the very detail of the words in the curse uttered by Lady Mabella, Edward’s name was no longer that of Tichborne. Not expecting ever to inherit the Tichborne title, Edward had obtained royal licence to change his name to that of Doughty in order that he qualify for a considerable bequest from his cousin Elizabeth Doughty in 1826. He had promptly married, to a relative of the (Catholic) Duke of Norfolk, their only son, Henry Doughty, dying in childhood in 1835.

On inheriting the baronetcy, the 9th baronet, had promptly revived the Tichborne Dole, presumably with intention to be both charitable and to allay the Tichborne Curse.

The story told above is a much shortened version of that which might have been told in a cottage of an evening in front of the fire.

=> a more detailed version about the Tichborne Curse is available here.

Perhaps, the tradition of the Dole and the associated Curse, once well known across Hampshire, would have been forgotten amongst most of the villagers of Aldershot by 1853, but for the recent news of the death of Sir Edward, in March.

His obituary was published in The Illustrated News noting that the title and estates therefore would pass to Sir Edward’s only surviving brother James. He had been the chief mourner at the elaborate funeral and was the third and only surviving of the seven Tichborne brothers. (The fourth, fifth, and seventh brothers had died much earlier, the sixth doing so in November 1849; all were without a male heir.)

It seems likely that ‘The Illustrated’ was delivered regularly to the Pall Mall residence of Charles Barron Esq. but was not otherwise in general circulation in the village. The details of the marriage and heirs of Sir James Francis Tichborne, now the 10th baronet, might therefore not have been widely known.

He had married Harriette-Felicita, the French love child of Henry Seymour M.P. from his affair with the supposed love child of a direct descendant of Louis XIV of France. Seymour was himself a direct descendant of the eldest surviving brother of Jane Seymour, the mother of the only son of Henry VIII of England.

-

- There is further spice to the tale, as Roger Charles Tichborne, now the heir apparent had boarded a ship for South America at the start of March, unaware of his status with respect to the Tichborne estate. The next year he would be reported as lost at sea, his existence much later becoming the subject of a famous legal case known in the press as the Tichborne Claimant.

=> Additional information about the Tichborne family (with family trees).

27th March 1853

Easter Sunday 1853 was a special day in so many ways, especially for Reverend Carey. He would have been particularly keen to congratulate Mr Richard Allden before he left on becoming a grandfather. Reverend Carey had conducted the wedding of his daughter Mary Ann at St Michael’s in April the previous year. However, the curate would not have been able to meet Richard at Matins on Easter Sunday as he would be elsewhere attending the christening of Elizabeth his first granddaughter. The Reverend Henry Albany Bowles, a fellow graduate of Carey from Oxford, conducted the service at St Mary’s Church at Send and Ripley.

The parents of the child were cousins twice removed. Mary Ann’s husband was John Allden, the third son of a farmer from Frensham. That was Richard’s eldest cousin Joseph Allden. Many across the extended family had benefited from bequests in 1810 by Richard’s great uncle, George May. However, Joseph’s father had inherited the residual of the estate, both freehold and copyhold. including the farmland at Ash. The marriage of their two children now linked Richard’s side of the family even more closely with the senior branch of the family.

Richard Allden and the curate had come to know each other very well. Richard been a churchwarden several times. More than that, Henry would doubtless recall Richard as the youngest of the four patrons at his appointment as curate back in 1838. Perhaps, Richard would be back in Aldershot for Evensong.

=> More on the Allden family

29th March 1853

Tensions between Russia and Turkey continued, the Czar confident that the latter was so much ‘the sick man of Europe’ as to be in terminal decline. There was optimism that a solution might be found, however, as indicated by Queen Victoria in her letter to her Uncle Leopold, King of Belgium:

Buckingham Palace, 29th March 1853

=> April 1853

Edited on 24 February:

* Close inspection of the Crondal court records by Sally Jenkinson has established that the Tichborne family never owned the so-called Manor House.

** No evidence has been found to support the notion that Richard Tichborne built a house which later become known as the Union Building.