August

This was a month for cottagers to enjoy what had been growing in their gardens. The seasonal rhythm of the year now providing the promise of delivering ripe fruit and vegetables all across the village.

Village communities fed themselves. Even the humblest of cottages had something of a garden attached. Whilst some would be cropping early apples, the reports from the markets were of cherries and damsons as well as apricots and plums. Gooseberries, blackberries and raspberries were to be found in gardens or growing in the wild.

It was not too soon to start a store of produce for the winter months. Thoughts when digging up the early potatoes would turn to the choice of other crops to plant for harvest later in the year.

The policy of the parish officers of the Vestry favoured outdoor relief, providing land which could be worked by those unable to bring in wages. Nevertheless, a further repeat of a poor harvest followed by an especially miserable winter could threaten months of hardship.

The weather during the previous twelve months had been disappointing in both respects. Who knew what the future would bring? While there was good light, the days still long, all members of the household, including children, would be working in their gardens, as later would many in the fields for their masters.

That said, at the close of each day, there were thirsts to be quenched. The Red Lion and the Bee Hive, the two public houses at either end of the village Street, would both be open for business.

The Red Lion Inn was not far from the village green. It marked the end of the Street where the Ash Road began, leading down to the Blackwater River and the County boundary into Surrey. Red Lion Lane was to the right with its slow incline up to where Church Lane East became Church Road.

Little doubt but each hostelry had its own regulars, with separate rooms to cater for those of different social standing. The uppermost map, made in 1841/42, contrasts the immediate catchment of the Bee Hive, in what was the commercial centre of the village, with that of the less populated catchment of the Red Lion. The lower map, made in 1855, highlights the proximity of the Red Lion Inn to the residences of three of the four leading figures in Aldershot’s elite: Richard Allden of Elm Place; James Elstone of Aldershot Lodge and Captain Newcome at the Manor House. Charles Barron Esq. of Aldershot Place was the fourth, latterly Chairman of the Vestry.

The recent meetings at the Red Lion about the enclosure of Aldershot Common had generated an additional buzz of excitement. There would be plenty to discuss of an evening. That would continue with the experience of a surprise visit. August was to be an eventful month in the history of the village, although tinged with the sadness of infant death.

Red Lion Inn

Management of the Red Lion had previously been with local families, dating back to Joseph Hart in 1800, his widow and then his son until the 1830s. Frederick Freeman took over the Red Lion in 1838. The carpenter John Kimber was installed as landlord by 1841 until 1847.

Now owned by a Mr Barratt, George Falkner had been the landlord at the Red Lion for about five years. The 1851 Census listed him as both an inn keeper and a plumber. The latter was the trade of his father Thomas with whom he had been living along the Borough in Farnham in 1841 as the eldest of five children.

George had been born in Farnham in 1820, marrying there in April 1845. His wife Ann was the daughter of Edmund Elseley, a farmer from Elstead. Before moving to Aldershot, George and Ann lived along the Farnborough Road, their son Frank baptised in 1848 at St John the Evangelist in Hale.

=> More on the Red Lion Inn and former landlords

Thursday, 4th August 1853

The farmers had reasons to be in a positive mood, not just because of the improvement in the weather. The weekly market at Farnham was experiencing brisk trade for wheat. Prices varied from £10 – 10s. to £16 per load, even better than two days before when they fetched £9 – 10s to £15 on the Tuesday at Alton.

There had also been the positive outcome from the Inclosure Commissioners to the proposal that the 2,715 acres of Aldershot Common should be enclosed. This carried the prospect that farmers could bring additional land into productive use.

The Provisional Order, made two weeks ago on July 18th, also ensured that some common land would be kept for common purpose. Fifteen acres were to be put aside “as endowment for [a] national school”, in addition to the ten acres for the “labouring poor.” The four acres of the village green were to be preserved as common land, still referred to as Paine’s Green, after James Paine who had once held the smithy.

What was unclear when this would all come to pass. The neighbouring parish of Farnham had received Provisional Order for lands in Badshot and Runfold back in April, but nothing was known of progress on that either.

The inner-wheels of government were still in motion, however. The Secretary of the Inclosure Commission had written to Home Secretary Palmerston on that very day. He had forwarded the draft of a Bill for Parliamentary approval for as many 27 applications for the enclosure of common land; those for Aldershot and Farnham were both included in the accompanying Special Report.

The civil servants at the Home Office hastily sent the Report and Bill to be printed “with as little delay as possible.” The letter sent by the Inclosure Commission was annotated to the effect that the Bill was to be “introduced as soon as possible.” Those civil servants were conscious that the current session of Parliament was shortly to be dissolved. Authorisation to enclose Aldershot Common would form part of the Commons Enclosure (No. 3) Bill which would be put to Parliament alongside the Copyhold & Commission Continuance Bill.

Saturday, 6th August 1853

The Hampshire Chronicle echoed the importance of the upcoming harvest, also warning of high prices,

“Attention is now naturally directed to the harvest, and, under the inspiring influence of returning sunshine, we are enabled to take a calmer view of the prospects before us. ..

“For several consecutive years previous to 1852 we had good crops; still Great Britain has been capable of consuming the whole of supplies other countries have been enabled to furnish.”

Stocks from overseas were low, with only America having capability to supply sufficient:

“the importance of our own harvest can therefore be scarcely over-rated;

and the next month is likely to prove a period of great excitement.”

Ann Bedford

Locally, the news that day was of the death of Ann Bedford. There were two of this name in the village, thoughts likely turning to the teenage Ann who was a domestic servant for the Elstone family at Aldershot Lodge.

The tragedy instead was for the loss of her young cousin, the infant daughter of George Bedford who lived up at Deadbrooks. Baptised in September 1852, she had died aged only 11 months. Her mother Eleanor had reported the cause to be ‘teething convulsions’.

So prevalent was this attributed cause of infant mortality, it was termed ‘dentition’. It was associated with any negative outcome following the eruption of the first teeth. That included the unwanted effects of the various attempts at remedy during a time of poor sanitation. This period in a child’s life was also when weaning onto cow’s milk would start.

Sunday, 7th August 1853

As though to highlight the significance of vital events in the village, there were to be three christenings at Matins this Sunday.

Jane Rebecca Bedford

At the first, what was intended as a happy event for Thomas and Mary Bedford would surely have been tinged with the sadness for the death of Jane’s baby cousin Ann. She had been the daughter of Thomas’ younger brother George.

Thomas Bedford was a farm labourer in a tied cottage on Church Hill belonging to the Aldershot Lodge estate. He was the father of the Ann Bedford who was now in domestic servant up at the Lodge in the household of James Elstone Junior and his wife Caroline (‘Mrs C’).

The infant Jane was their eleventh child, her ten older siblings all born in Aldershot, with baptisms dating from 1836. The four eldest were daughters, born about a year apart; their younger brother Thomas, born almost 18 months after the fourth, was the sole boy between two sets of daughters.

There had been more than enough daughters in the Bedford household when Ann had secured her position at Aldershot Lodge. Charlotte, the next oldest, also went into domestic service. By 1851, at the age of 13, she was in the household of Thomas Eyre, an established grocer in the Borough in Farnham. Such opportunities brought in extra income for the family and certainly meant one less mouth to feed. This was also a chance for the girls to do more than be minding children at home.

Thomas Bedford was from a local family, his father Charles baptised at St Michael’s Church in December 1790. His mother Sarah was from Pirbright, where Thomas had been born in 1813. His parents had been based on Church Hill in 1841, his father Charles presumably then working for James Elstone Senior. Thomas and Mary were based in a cottage there too. Thomas’ parents later moved to live along North Lane.

Thomas Bedford and Mary Hockley had married at St Michael’s Church in Aldershot in June 1835. Mary had been baptised in 1814, in Nutley, 20 miles distant from Aldershot in central Hampshire. Perhaps Mary had been in domestic service closer to Aldershot at the time of the marriage.

James Thomas Cooper

James was the next child listed in the parish baptismal register. He was the third child for George and Elizabeth Cooper, their two young daughters also born in Aldershot. The parents, however, were both born outside the village.

They lived in a tied cottage on the Aldershot Place estate on which George was a farm labourer. Baptised in Farnham, he had married Elizabeth Smith at the church in Hale in 1847. Before that, in 1841, he had been employed at Dockenfield where he stayed with his brother and sister. Elizabeth was the daughter of a gardener from Weyborne,

-

- The elderly James Cooper lived with his son William at Dog Kennell, not far from Weyborne. This was not George’s father but maybe he was a relation.

Peter Robinson

The infant Peter was one of six children of William and Caroline Robinson. The previous five had also been baptised at St Michael’s Church, between July 1844 and October 1851. William was an agricultural labourer, he and his family living in a cottage at West End, close by Thomas Smith’s Rock Farm.

Reverend James Dennett would come to realise that there were many of the name Robinson in the village. The 1851 Census recorded as count of 27, second in number only to those of the Barnett family. Some owned land, many more were labourers on the land. Several had the same Christian name. These families had connections through marriage with many of the other well-established farming families, both throughout the parish and across in neighbouring Ash.

William was the son of the tenant farmer George Robinson; his mother had been Mary Avenell when she had married in in Farnham in January 1813.

-

- The marriage register had no space to record the name, nor the occupation, of the father of Mary Avenell. However, a man called John Avenell, aged 70, was in the household of George and Mary in 1841. His death was registered in Farnham in 1842, aged 71.

- He was not the John Avenell who died in 1844, aged 84, who was recorded by the 1841 Census as the farmer at Hale Farm in the tithing of Badshot. In 1851, his son, James Avenell had taken on Hale Farm, a hop planter of 156 acres employing 17 men and 3 boys. His extensive landholdings included 38 acres in Aldershot, mostly up at Deadwoods.

William Robinson had been baptised at St Michael’s Church, in May 1821. Before his marriage in 1843, he was his parents’ household in a house and garden owned by the widow Ann Robinson in North Lane; his father George was working as a tenant farmer. Others in the house in 1841 included James Pester, aged 5, the son of William’s older sister Ann. She lived next door with two small children from her marriage to John Pester in Aldershot in 1834. He was an agricultural labourer from as far away as East Budleigh in Devon.

William and Caroline had married in Bentley, which was where the 1841 Census recorded the child’s mother as Caroline Young. She was in the household of her uncle, Richard Young, an agricultural labourer in the village of the Eggar family.

-

- The influence of the Eggars is clearly evident in the biographical history of the Young family. Caroline, born in Binsted, had been baptised at St Lawrence’s Church in Alton in 1822, the daughter of William and Hannah Young. Her father died in 1840, buried in Aldershot that October. This likely prompted Caroline’s move to be with her Uncle Richard’s family in Bentley. Richard’s first child Elizabeth had also been baptised in Aldershot, in July 1817 shortly after his marriage to Catherine Barnard in Bentley in February 1817. (Catherine Barnard was listed in the Census as having been born in Aldershot around 1795 although no baptismal record is found.)

- William was the older of the two brothers, sons of William and Elizabeth Young. William was baptised in 1790 at St Peter’s Church in Ash, his parents then resident in nearby Normandy; Richard was baptised later in Aldershot in 1796 at St Michael’s Church.

=> The Families Robinson [to be added later]

Monday 8th August 1853

Any in the village keen to see progress in the matter of the enclosure of Aldershot Common would have been pleased to learn that the Copyhold & Commission Continuance Bill and the Commons Enclosure (No. 3) Bill had now been laid before Parliament. Aldershot was amongst the 27 parishes with applications for enclosure listed in the schedules attached to the Bill.

Tuesday 9th August 1853

Progress was indeed swift. The Evening Mail and the evening edition of the Sun both reported that the Copyhold & Commission Continuance Bill and the Commons Enclosure (No. 3) Bill were read a second time in the House of Commons. This was, perhaps, only noticed then by Charles Barron Esq. when at his London address in Pall Mall. News might have been relayed to Captain George Newcome by his brother-in-law Ross Donnelly Mangles, the Member of Parliament for Guildford.

Wednesday, 10th August 1853

None in the village would have read the addendum included by the Limerick Chronicle to its report of the Queen’s review of her troop at Chobham Common. The Irish newspaper confided,

“The Government has secured, for next year’s Camp, ground very superior to that of Chobham, on Aldershot Heath.”

This rumour was repeated verbatim in editions across Ireland on the following Saturday, notably in the Cork Constitution, the Newry Examiner and the Louth Advertiser, Roscommon & Leitrim Gazette.

No sign of this ‘story’ is found in the searches of the newspapers on the British mainland, however. Seemingly, the article had not been noticed. However, this ‘news’ could be taken as suggestion that the prospect of success for Viscount Hardinge’s plans was being taken for granted in some circles. He had, of course, secured neither approval nor finance for a permanent camp of instruction, a wish he had express in June to Lt. General Colborne (Baron Seaton).

Friday, 12th August 1853

The funeral service this day, the seventh by Reverend James Dennett, who was still only in his fifth month, had an added sense of intimacy. He would be saying prayers for the death of the niece of his parish clerk. In his combined role as village sexton, Thomas Attfield had been called upon to dig the grave of the daughter of his sister Eleanor. The dead child was only eleven months old.

Ann Bedford

Baby Ann’s father was George Bedford, an agricultural worker. George and Eleanor had married in January 1838. They lived up at Deadbrooks, baby Ann the latest of eight children, the eldest, at 13 years old, listed as a seamstress.

George had been baptised in neighbouring Ash. His mother Sarah was born in Pirbright, as was George’s older brother Thomas. George’s father Charles had been locally born.

Eleanor was the tenth of George and Nimmy Attfield’s thirteen children. Then there was the large number in the Bedford family, twenty of that name recorded in the parish by the 1851 Census. There would be many at the funeral.

The child’s mother went to Farnham to register the death on the same day. Making her mark, she indicated that she had been present at the her daughter’s death and stated that the cause was attributed to teething convulsions.

Saturday, 13th August 1853

This week’s edition of the Hampshire Chronicle had several items of interest.

The Chronicle remarked that the prorogation of Parliament was expected soon, probably during the next week. Lack of parliamentary approval would mean delays to the enclosure of Aldershot Common.

Given the excitement generated by the prospect of enclosure of Aldershot Common, two more items had particular relevance.

The Valuer acting on the matter of the Ash Inclosure for road contractors had placed a call for tenders “for the forming and making of roads over the waste lands of the Manor of Ash.” The paths that crossed Aldershot Common to the Canal Wharf from the settlement around Drury Lane needed comparable improvement.

There was also a notice proposing the exchange of property between Dame Jane St John Mildmay of Dogmersfield Park and Charles Edward Lefroy of Crondall. These exchanges, if judged to be beneficial by the Inclosure Commissioners under “The Acts for the Inclosure, Exchange and Improvement of Land” would appeal to farmers seeking efficiencies.

Elsewhere in this Saturday’s edition of the Chronicle, the Mark Lane Express column noted that the weather had been fine during the greater part of the past week. However, even with a few more weeks of settled weather, it conjectured that the quality of the harvest might be improved, but not the yield.

“It is the opinion of some that that the produce of wheat will prove the smallest that has been harvested in these islands since 1816.”

The recent rise in prices was due to a mix of circumstances:

“deficient Wheat harvest in Great Britain and France; a failure of that crop in several of the southern countries of Europe; short stocks everywhere except in America; .. imminent danger of the quarrel between Russia and Turkey leading to a war in which England and France may become involved.”

Few might have paid much to heed to news that the Succession Duty Act had received its royal assent. This was essentially a wealth tax which required a complex of tables to determine the level of tax to be paid on the inheritance of family property. However, some had argued during the preceding parliamentary debates that it would be damaging to the smallholder, more so than to those owning the great estates, and would undermine the viability of the yeoman farmer.

There were continued mixed opinions about the prospect of war. The reports earlier in the week were that the British Government had received telegraphic dispatch from Vienna that the Czar accepted the proposition of the four powers (of Britain, France, Austria and Prussia). However, there was no certain confirmation of this. A letter from Paris, dated Friday, stated that the Sultan had accepted the Vienna proposals but awaited news that the Russian troops would vacate the territory it had invaded.

Wednesday, 17th August 1853

Locally, news was of another death in the village. Once more, there might have been confusion about the identity of the deceased, Stephen Barnett also being the name of James Elstone’s father-in-law, Caroline’s father. The sad news was instead for the loss of an infant, aged 19 months.

The child’s cause of death, reported much later, was attributed to ‘Hooping Cough’; he was said to have had consumption since birth.

The funeral was set to take place at the end of the week.

Thursday, 18th August 1853

The Commons Enclosure No. 3 Bill received its third reading in the House of Lords. It then later went through its final Committee Stage in the House of Commons, as reported by the London Evening Standard. This would be greeted with delight by those who had proposed the enclosure of Aldershot Common.

Elsewhere in the village, a sadness fell across the length of the village with the loss of a third infant, that of Jesse Stonard, not yet 18 months old. His death, was attributed to Hooping Cough, as well as to ‘Dentition’, the high temperature due to teething.

That funeral would be set for Wednesday. The child’s mother Agnes would later travel to register the death in Farnham.

Saturday, 20th August 1853

Stephen Barnett

First, there was the funeral of young Stephen, 19 months old, born to George and Rebecca Barnett. The funeral held for his mother in June was still in recent memory for many of those gathered at the parish church.

Rebecca’s death was attributed to having suffered consumption over a period of four months until her death on June 4th. This diagnosis had not been medically certificated; it was instead stated by George’s sister Jane Bullen who had been in attendance. The cause of death, again not certificated medically, of the infant Stephen was reported by George’s sister Harriet Derbridge. She attributed it to ‘Hooping Cough’, but also stated that the child had suffered from consumption since birth.

The family lived on Drury Lane in a cottage rented from Mr Hall. At the start of 1853, George, an agricultural labourer, had a wife and four children. Now he was a widower with three small children. His world had been turned upside down.

Locally born, George was baptised in 1822 to parents James and Elizabeth Barnett. Before his marriage in 1845 he had lived in the family home in the cottage and garden across the Street from the Drury Lane. Known as Culls, this was rented from Richard Allden.

George’s widowed father James still lived at Culls, George’s married sister Jane and husband James Bullen having moved in as lodgers. They now had a small baby of their own, baptised in December 1852. Bullen was a carpenter who had served his apprenticeship in the village of Shere, on the other side of Guildford.

It seems probable that one of George’s sisters would have helped by taking care of his four young children after his wife died. Harriett seems the more likely to care for Stephen. She was in receipt of parish relief, staying in a cottage owned by Mrs Benham. This was in a locality known as Bakers, about three hundred past the Bee Hive Inn, at the northwestern end of the Street.

Harriett had stated she was present at the child’s death. With children of her own, it seems plausible that Stephen was in her home when he died. Harriett’s own daughter Elizabeth, aged six, had developed what seemed like Hooping Cough.

George and Rebecca Chandler had married at St Peter’s Church in Ash in 1845. Their eldest child Elizabeth, probably now also deceased, had been christened there in January 1846. Two of their children, Jane and William, had been born in Pimlico, baptised at St Peter’s Church in Eaton Square in 1847 and 1848, respectively. George and family had returned to Aldershot by 1850, their fourth child then baptised at the parish church. The 1851 Census does not include Elizabeth who, had she lived, would have been not much more than five; child mortality in London was high.

Commons Inclosure Bill

On this same day, the Government used the last of the Parliamentary session to push through had a long list of bills.

Viscount Palmerston was in the House of Commons having to speak on many matters as the most senior member of the Government. As Home Secretary, it fell to him formally to introduce the Commons Inclosure (No. 3) Bill.

The Bill was duly passed on that same Saturday, the day of prorogation, later to be given royal assent.

The Bill was duly passed on that same Saturday, the day of prorogation, later to be given royal assent.

Aldershot was 19th on in the list of parishes named on the Schedule to the Act, the related comment in the Special Report stating,

“This inclosure will lead to the reclamation of a large tract of land, now almost useless.”

Tuesday, 23rd August 1853

Three days later, the Morning Post carried a report of the very long list of public and private bills which had come into law. That included the Commons Inclosure (No. 3), as it was known. No details of its contents were given.

Just who in the parish had learnt that the proposal to enclose Aldershot Common had now secured government approval is not known. Once again, Charles Barron Esq. and Captain Newcome were the most likely to have been kept informed.

Wednesday, 24th August 1853

Jesse Stonard

Locally, Reverend James Dennett was called upon to bury yet another infant, the fifth in as many months and the third in less than a fortnight.

The funeral brought together the Stonard and Nichols families, the two largest families of brickworkers in the village. They had been assembled before for Jesse’s baptism as recently as January of this year.

Jesse had been the fifth child of Henry and Agnes Stonard. The family were lodging in the household of Agnes’ parents, James and Eleanor Nichols, at West End in the cottage rented from Stephen Barnett.

The child’s father Henry was a tilemaker, the son of James Stonard, the Master Brickburner. Henry and Agnes had married in 1844.

This would be the young curate’s first formal encounter with the families of workers in the village’s brick business.

Newspaper Reports

The nation’s press was full of the comings and goings of the members of the Government as well as the upper echelons of society.

First, the daily newspapers were reporting that Viscount Hardinge had been attending Queen Victoria at her holiday home at the Osborne estate on the Isle of Wight. Doubtless, Prince Albert would have taken the opportunity to be briefed by Hardinge about his plans for the location of a camp on Aldershot Common.

Then the Portsmouth Times and Naval Gazette reported that General Viscount Hardinge and his staff had arrived in Portsmouth that evening. He was to dine as the guest of Major General James Simpson, the Commander of the South-West District at Government House. Simpson was a graduate of the University of Edinburgh and a contemporary of Adjutant-General Sir George Brown, the latter a staunch opponent of Hardinge’s reforms. Notwithstanding, this was another suitable opportunity for Hardinge to share his thoughts about the location of a permanent camp.

Thursday, 25th August 1853

The next day, the Court Circular noted that Viscount Hardinge had returned to London that morning. He maintained a large household at his residence in Stanhope Street, north of the Euston Road. As many as ten staff were employed to his wife, daughter and himself.

He had a seat in the House of Lords and although a member of Cabinet, his duties as Commander-in-Chief of the Army involved a busy schedule that kept him away from obligation to engage much in Parliamentary business.

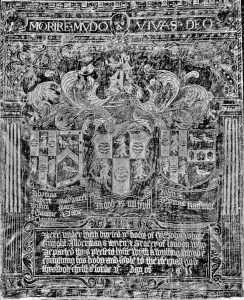

The Commander-in-Chief travelled down to Aldershot Common to inspect the site. He lodged that evening at the Red Lion Inn.

Friday, 26 August 1853

The story goes that later that day, Viscount Hardinge called for paper and ink and then penned a letter to Prince Albert. In this, Hardinge recommended that the camp should be established upon Aldershot Heath, writing “to say that he had ridden over the ground from the slopes of Caesar’s Camp to the Canal, and that the area was admirably suited for an encampment for a Division, reserving all the rest of the ground for the purpose of manoeuvres.” [Cole, 1951]

Hardinge indicates that he intends to set off to reach for South Park, his residence in Kent, by the evening.

Just how quickly news of that visit had spread across the village is moot. Likely, Hardinge had arrived at the Red Lion at dusk, late into the summer evening. It is not known whether he was in uniform, nor whether he was accompanied by any other officer. However, is unlikely that his visit went unnoticed. One can imagine James Hone, the local veteran of Waterloo, enjoying a pint that night at the Red Lion, and noticing the missing left hand of the acknowledged war hero of that campaign.

This was an iconic moment, with memories both real and manufactured, enhanced with each retelling.

One thing is certain, even with this visit to the Red Lion where the inquiry meeting for the enclosure Aldershot Common had been held. Neither Commander-in-Chief Hardinge nor Prince Albert had slightest inking that Government approval and Royal Assent had already been granted.

Saturday, 27 August 1853

Indeed, no mention was made of Aldershot was made in the Hampshire Chronicle which included the enclosure legislation as amongst the acts passed at the close of Parliament on August 20th.

Viscount Hardinge would write in positive tone in letter headed Saturday (but otherwise undated) to his Adjutant-General, Lt General Brown, with the words,

“I rode over the ground at Aldershot & found I would get home for dinner but that I should be too late for any meetings in London ..

“The ground around Aldershot is excellent for our purpose.”

Monday, 29th August 1853

The national press began its extensive coverage of the military career another renowned military commander. Lt. General Charles James Napier he had died at five o’clock that morning at the age of 71. He was well connected by birth, his mother a descendent of Charles II, his father from John Napier of Merchiston (of logarithm fame).

The Sun carried a front-page eulogy of Napier on the Tuesday. The article included favourable references to Viscount Hardinge, as did the account in the Manchester Times on the Wednesday.

-

- The careers of Hardinge and Napier intertwined. Both were severely wounded during the Peninsular War. Both fought at Albuera; Napier crediting Colonel Hardinge, as he then was, for the tactics which saved the day. Napier had then risen in the Bombay Army to become Commander-in-Chief in India. Governor General Hardinge returned the compliment. He wrote to praise James Napier: “He is, besides his warlike qualities, a very fine fellow. .. practicable, good-tempered, & considerate.”

Civil Registration

Back in Aldershot, Agnes Stonard and Harriet Derbridge visited Farnham to register the deaths of two of the infants who had died during August. Perhaps the two women had travelled together; it was about an hours’ walk via Weybourne to the centre of Farnham from their neighbourhood. Agnes was the mother of the infant Jesse, Harriet the aunt who had sat by the bedside of Stephen.

The details concerning the deaths of the two children were listed consecutively in the register, entered straight after those for Ann Bedford. Her death had been attributed to ‘Teething Convulsions’. The earlier death of Francis Barnett in late May had also been attributed to ‘Dentition’ following three days of convulsions.

None of the toddlers who had died were first children, born to young inexperienced mothers. All appear to have been teething, likely weaned from breastmilk to cows’ milk. Stephen’s death, and his mother’s death in June, had been attributed to months of having suffered from ‘Consumption’, another term for tuberculosis (TB). Milk in the 1850s was unpasteurised and therefore a potential source of Bovine TB. Hooping Cough had also been listed as a cause of death.

No doctor has been present at any of those infant deaths. All the entries were signed off by John Mayor Randall, the surgeon and general practitioner, aged 66. Perhaps Registrar Randall, whose residence was along the street in Farnham known as the Borough, was confident of making a judgement on the basis of the symptoms reported by the two women. It is unknown whether or not he would have been prompted to investigate this cluster of infant deaths, there being no resident doctor in Aldershot.