The Village as Place

William Cobbett evoked a sense of rural idyll for the place, in 1835 describing Aldershot as “an agricultural and nice productive little parish”. This was amplified in the various guides made for the affluent middle class who would later travel to visit ‘the Camp at Aldershot’. One, written in 1858, published in January 1859, stated:

“Yea, true it is, that not more than four years since, Aldershot was one of the most pleasant and picturesque hamlets in Hampshire. … The scenery away from the Heath was most rural and romantic, and there were spots … which could vie with any in the neighbourhood as a beautiful and luxuriant landscape. The lanes around were … especially pretty, secluded, and rural …”

(Sheldrake, 1859)

The language used later in the Victorian County History was more prosaic, but it ensured that a sense of the idyllic would find repetition in subsequent histories:

“Previous to 1855 Aldershot was one of the most pleasant and picturesque hamlets in Hampshire, consisting of the church, the two important houses called Aldershot Manor and Aldershot Place, two or three farm-houses, and the village green …”

(Page, 1911)

Aldershot and Farnham

Aldershot is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. The earliest reference to the place, in one of various spellings, appears over a hundred years later, in 1248, within the manuscript returns written by the monks of the Winchester Priory which by then was dedicated to St Swithun, a former Bishop of Winchester.

Before the Norman Conquest of 1066, the Kingdom of Wessex had been divided into areas called Hundreds and Aldershot was one of the tithings, a further sub-division, of the Hundred of Crondall. When King Edgar of Wessex confirmed the Priory as owner of the of Crondall Hundred n AD 971, the course of the River Blackwater was used to define its southeastern boundary. Thus, Aldershot lay on one side of the Blackwater and Farnham lay on the other.

The Domesday Book declared that the Hundred of Crondall had ‘always belonged to the Church’, an ambiguity which would be the basis of later dispute between Bishop and Prior. The Domesday compilers ignored, but maybe were ignorant of, the mention of Crondall in Alfred’s will of 875.

Ownership by the Church, and by the Priory in particular, therefore survived the allocation of land by William the Conqueror to his supporters. It would also survive the Dissolution of the monasteries almost 500 years later, through transfer to the Dean of the Cathedral. This had consequences for both landownership and governance.

Farnham was also included in the Domesday Book, definitely recognised as a possession of the Bishop, having been granted to the Church before the time of Bishop Swithun. Domesday recorded 58 villagers, 20 smallholders and 11 noted as ‘survus’, variously translated as serf or slave.

The strategic position of Farnham meant that it served as a staging post for journeys to London from Winchester, the ancient capital of Wessex.

Vol. 1. of Maps. Drawn in 1830 (1: 76500) Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Chapman and Hall, London, 1844.

Vol. 1. of Maps. Drawn in 1830 (1: 76500) Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Chapman and Hall, London, 1844.

The Winchester Bishop maintained his palace at Farnham which developed into an important market town. Bishop Henry of Bois fortified the palace as Farnham Castle in 1138.

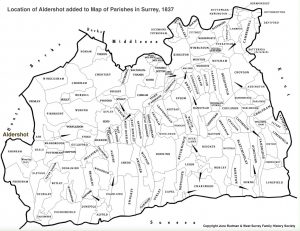

Farnham was connected with Godalming and Guildford along the River Wey and thus was included as part of Surrey. Crondall, and therefore Aldershot, formed part of Hampshire and under its political and economic jurisdiction.

-

- This distinction is significant as the County, and within it the Parish, was not only the building blocks of ecclesiastical administration but also served as the basis of that of civil authority and governance. (Many maps were drawn and published as County maps.)

The parish of Aldershot was therefore borderland. But for the course and turns in the Wye and the Blackwater, the latter often not much more than a brook, Farnham might have been to be reckoned as within Hampshire, Aldershot then almost certainly to be acknowledged as one of Farnham’s parishes if not actually forming part of it.

Notwithstanding, the reforms of civil administration during the 1830s and 1840s did recognise the close socio-economic relationship between the Aldershot and its market town. Farnham became the designated place for the registration of Aldershot’s births, deaths and marriages and the early censuses of population; the new Farnham Poor Law Union was designed to include the parish of Aldershot. Policing and the administration of the law remained with the county; that was also the case for the parliamentary electoral divisions, even after the 1832 Reform Act.

The names of places and parishes in Surrey are mentioned frequently in the history of this village, especially as places of birth and baptism for its inhabitants.

Village Settlement

As is still often the case in rural England, the oldest building in the village of Aldershot was the church. The tower of the Church of St Michael the Archangel dominated the skyline from a high vantage point. Weather permitting, the view from the top afforded an impressive panorama. To the north, down Church Hill, past the smithy and over the rooftops of the cottages on the other side of the village green, was the wasteland which separated the village from Farnborough. Variously called Aldershot Heath or Aldershot Common, the rough terrain was crossed by the Basingstoke Canal and the Turnpike Road, the latter from Farnham to Farnborough and onto London.

Ordnance Survey, First Series, 1:63360, Sheet 8, 1816. The British Library, www.bl.uk

Ordnance Survey, First Series, 1:63360, Sheet 8, 1816. The British Library, www.bl.uk

https://maps.nls.uk/os/6inch-england-and-wales/info1.html

A patchwork of cultivated fields was spread out closer in. Much of that land had been taken by encroachment over the centuries from the edge of a heathland which even in 1851 took up two-thirds of the 4,400-acre extent of the parish.

The village green at the foot of Church Hill was closer yet. The smithy was on the near side and one of the two remaining potteries, was on the other, along which ran a road was called Aldershot Street. The Red Lion Inn was at one end, where the Street became the road to Ash; the Bee Hive Inn was at the other end, by Drury Lane which led up the hill towards the Heath. The area around the Bee Hive Inn was the nearest the village had to a centre of industry and commerce; it included the main village shop, the bakery, the laundry and a pottery.

To the west and the farms at Ayling and West End, lay the parish and county boundary. Beyond that was Upper Hale (‘Heal’), and the rise of Hungry Hill and Farnham Park. The latter formed part of the estate of the Bishop of Winchester. William Cobbett had been employed as a farm labourer there in his youth.

Across the fields and meadows of Grange Farm to the south, there was a good view of the Hog’s Back. It stood proud on the elevated chalkland ridge along which ran part of the ancient ‘Harroway’. That had once connected Cornwall to the ports of Rochester and Dover, the route from Winchester to Canterbury made famous later as the Pilgrims’ Way.

To the immediate southeast of St Michael’s Church was an impressive row of elm trees, now in winter bereft of their leaves. This led to Aldershot Lodge and to another farmstead, suitably named as Elm Place. Further east, the land ran down to the bridge across the County boundary of the River Blackwater to the village of Ash, sight of the hamlet of Tongham hiding behind the trees of Aldershot Park.

The location would have seemed all the more agreeable to the incomer now that the railway provided a scheduled train service to and from London, a station established at Farnham by 1849, also having a stop at Ash. The timetables published in the weekly edition of the Hampshire Chronicle indicate journey times from Farnham to Waterloo of two hours or less. This was so much more convenient than having to go travel to Farnborough which had a station on the London to Southampton railway line; trains from London were operating there as early as September 1838; the full extent of the line was open from 1840.

The pre-paid Uniform Penny Post was also introduced in 1840. With that, an extensive network of railways and subsequent changes in stamp duties for newspapers, international, national and regional news were all delivered into households so very much faster than before. Again, Farnham acted as a hub, the village having an appointed official receiver of post, and therefore of newspapers, to collect and deliver to Farnham each day.

Population Count

When William Cobbett noted that Aldershot had “four hundred and ninety-four inhabitants”, he was clearly still using an official report from the 1801 Census. However, successive census counts had recorded a sizeable net increase in the headcount, up to 685 in 1841.

By 1851 there were 767 villagers and visitors recorded by the Census, 768 if you included the only locally born pupil who was counted amongst the 108 children and staff at the newly established District School set up to serve paupers from three Poor Law Unions.

The proportionate increase in the village in the fifty years from 1801 to 1851, from 494 to 768, was large (155%) but not as large as that experienced in England and Wales as whole, more than doubling (202%) from 8.89 to 17.93 million.

This was a period in which there was considerable net migration from villages to industrial towns and the country’s cities, including London which was about 40 miles from the village. The population in what would become the outer boroughs of London had risen from over 137,000 in 1801 to over 288,000 in 1851, up 210% in the fifty year period; the increase for inner London was greater still, up 227% across the fifty years from 879,500 to almost 2 million in 1851.

Population Composition

There were similar numbers of males (380) and females (370) amongst the known residents in the parish in 1851.

-

- The term ‘residents’ excludes eight visitors; regrettably it also excludes the unknown number of residents who were visiting elsewhere on what was Mothering Sunday in 1851.

The overwhelming number of adults (295/424; 70 %) had been married, that is, currently married (128 men; 121 women) or widowed (24; 22), rather than single (69; 60).

Age-Sex Distribution, Aldershot, 1851

Over four in ten (43.5%) of the resident population were children, that is, aged less than 15. There is also suggestion of longevity amongst the residents of Aldershot, with more than one in ten (78/763) of the village aged over 60. This is only partly the result of incomers who had retired into the village with an annuity from elsewhere. The substantial number (28) aged over 70 were all long term residents.

The general shape of the population pyramid is consistent with, although not evidence of, high fertility and net outward migration. The latter might explain some of the irregularities in the graph, especially the lower proportionate numbers of young men aged 15 to 24. However, it is not clear what to make of the apparent ‘missing men’ in the ‘40-44’ age group, which is not mirrored by women; the numbers, though, are small (9 men and 17 women).

-

- Not too much reliance should be placed on the self-reporting of age. Some of the unevenness in the graph, for both males and females, is likely the effect of ‘rounding up’ in the self-reporting of age, particularly from the 55-59 age category. However, the ‘missing women’ in the ‘35-39’ age group might have been associated with the hazards of repeated childbirth, but again the numbers are small (22 men and 12 women in that age group) and the differences might be down to random variation.

Occupational Activity

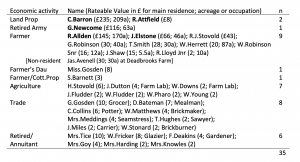

The following Table provides a summary of the occupations reported in the 1851 Census for the adults in the parish. The overall distribution was comparable with other villages located at a distance from the sea, according to estimates made from the ‘national’ rural database for 1851 created by Dennis Mills.

About one fifth of the heads of household were engaged in crafts, trades or commerce but the dominant industry was that of agriculture. In all there were about 18 farmsteads of varying sizes and nearly two-thirds of the households in Aldershot depended directly upon agriculture for their livelihood. Just over half of the men in the village were agricultural workers of one kind or another.

The 1851 Census used two main categories for agricultural workers, farm labourers and agricultural labourers. The former were generally on longer contracts and occupied accommodation owned by their employer. However, the use of the term agricultural labourer for the remainder can mislead by including both a ‘day labourer’, for hire on a lesser contract, and also an owner of a cottage and garden, with and without access to additional land on which to work on their own account.

-

- Information on the latter is not available from the census enumeration books but something of this can be gleaned from examining both the Poor Rate Books and the transactions recorded in the Crondal Court records.

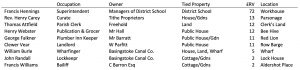

The professional class in Aldershot included the parish curate, the schoolmistress and a veterinarian surgeon, together with a list in rural trades: blacksmith and wheelwright, butcher and baker, cordwainer and shoemaker, carpenter and sawyer, carter and carrier, dairyman and grocer. Three of those in trade doubled-up as publican or innkeeper at the Bee Hive, Red Lion and Row Barge Inns. Other craftsmen were associated with making bricks dug from clay within the parish and pots with the fine clay taken from Farnham Park and the areas around the Blackwater. The Basingstoke Canal Company paid rates to the parish and also employed a lock keeper and a wharfinger.

People, Property and Power

Ownership of property underpinned the basis of power and authority. Unlike some rural villages, no aristocrat or squire ruled as a single dominant family in the village of Aldershot. Power, status and authority were diffuse, shared between the families of several established yeoman farmers, the owners of two grand houses and a small number with private means who had retired from London with annuity or pension.

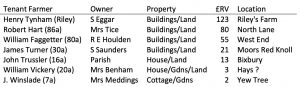

The seat of local governance in the parish was the Vestry, through which resident ratepayers had formal representation. An insight into who stood to exercise power and authority can be gleaned from review of the Poor Law Rate Books, especially when combined with knowledge from the Census.

The Rate Book for April 1853 lists 216 properties. Of the 162 residential ratepayers, 35 (one in five) were owner-occupiers. As enabled by the customs of the Crondal Hundred, these included both men and women.

What is shown against the name of each owner occupier, is the rateable value of the main residence and the known extent of their estate. Grouped by economic activity, the first listed are the land proprietors and (yeoman) farmers, about a third (12) of the owner occupiers. As will be shown later, these were the office-bearers in the Vestry, the men who were most influential in the governance of the village.

Those who were retired or living on an annuity included both Messrs Fricker and Deakins who had bought property having retired from London and the widows of farmers. Those women would not hold office in the Vestry, nor was their presence noted in the minutes.

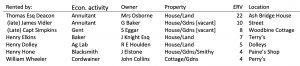

What is also notable is the extent of owner occupation amongst those classified by the Census as agricultural labourers or even as farm labourers, albeit for property having lower rateable values.

Business men like Messrs Tynham, Hart and Faggatter, all tenant farmers, also played an active role in village governance.

There was a variety of other tenancies. Five amongst the 11, in what could be regarded as tied premises, had special significance in the daily life of the village.

The first listed is the District School, a reminder that the school for 100 pauper children from three Poor Law Unions, which had been opened in 1850 up on the site of the former workhouse, provided employment as well as contributing to the parish rates. The next two listed are traditional for a parish, the accommodation available for the curate and the land that had been set aside to sustain the parish clerk. The role of the parish clerk, dating back many centuries in Aldershot, was to keep the church in good order; it also combined with the role of sexton, charged with digging graves for the dead. Three of the tied premises were the three public houses in the parish, at least two of the landlords also having other occupations.

The remaining 110 residential properties, two-thirds of the total, were all let for rent. Although some were owned by farmers for their employees, in the majority of instances the cottage was let by someone other than an employer, and several by an absentee landlord. Three properties were let to gentlemen, including Thomas Deacon, a long-time resident who also kept a house in London.

What Next

Not listed or named above are over one hundred other tenants in properties having rateable values less than £4. Most of these families occupied a cottage with a garden, that latter used to grow foodstuff.

Stories of those families would not feature in a top-down history which had its focus only on the office-bearers of the Vestry. One device for bringing their story front stage is to include a focus on the significance of other aspects of village life, namely, of births, deaths and marriages. Contemporary information about these vital events is represented by the baptisms, burials and weddings recorded in the parish registers..

All that said, the scene now set, click below for the story of the villagers as it begins on New Year’s Day …