Wednesday, 1st June 1853

The conflict between Russia and the Ottoman Government had reached a stand-off. The Morning Post was reporting that the money markets were “heavy, in anticipation of the next demonstration that may be made on the Russo-Turkish question”.

-

- Protracted diplomatic activity was based at what was called ‘The Porte’, the central authority of the Turkish Government in Constantinople. The balance of view in news reportage to the general public was that outright war would be averted. The extended lines of communication between ambassadors and governments, meant huge delays, however.

In other, seemingly unrelated news, newspapers were reporting the preparations being made for the large-scale military exercise at Chobham. Troops from around the country had begun to assemble at the Camp at Chobham, with various activities scheduled to last at least two months from the middle of June.

From London Illustrated News

From London Illustrated News

As many as 8,000 men, 1,500 horses and 24 guns were expected to be mustered on the heathland in Surrey for drill, field operations and parades. As though to provide a diversion for the public’s attention, the press set out the list of regiments which would be taking part and details of who would be commanding.

The London Evening Standard that day had chosen to highlight its concern about the Alteration of Oaths Bill, then in its Second Reading in the House of Lords. The newspaper’s Leader Column argued that it was a backdoor attempt to allow Jews to sit in the House of Commons. The Bill was subsequently defeated.

Earlier, in April, there had been a majority within the House of Commons for a ‘Jewish Disabilities Bill’, of 288 to 230; not so in the House of Lords. The ‘Jew Bill’, so termed in the press, was opposed by the Earl of Shaftsbury and Bishop of Salisbury, for example, and it was subsequently defeated by a majority of 164 to 115.

-

- There had been several types of Oath, those during the reign of William III directed against “Catholic Pretender” and thus excluding Roman Catholics from public office. The provisions of the Catholic Relief Act of 1829 resulted in a separate Oath to allow Roman Catholics elected as Members of Parliament to take their seat, and there was a separate one for Quakers, “yet if a person of the Jewish persuasion [elected as a Member of Parliament] were to go into the House of Commons and take an affirmation” he would be required to do so as “on the true faith of a Christian.”

Saturday, 4th June 1853

Locally, the news around the village during the first weekend in June was mixed. Saturday’s edition of the Hampshire Chronicle confirmed what farmers already knew. After a prolonged cold Spring, the weather had eventually abated.

The milder temperatures were now leading to a good showing of young wheats and spring corn. Notwithstanding, the extent of land sown with wheat was down by 15 to 20 percent when compared with the previous year, which meant there was good prospect of favourable prices. That happy thought by the growers was offset, however, by concern about the ease with which supply would be procured from abroad, given the lack of duties levied on imported cereals since the repeal of the Corn Laws. Much would depend upon the prospects of imports from the Black Sea given present tensions in the area.

Francis Barnett

Up at the parish church, the Reverend Dennett was called upon to conduct the funeral of yet another infant in the village. Francis had been baptised at the church by his predecessor just over a year previously, in May 1852. Francis had been the third son of William and Esther Barnett. Their loss would have brought back memories of their two daughters who had also died as infants, aged one and four months, respectively, in 1847 and 1848.

William married Esther Newell in Aldershot in November 1844, aged 24 and 23. It had been Esther, not William, who was able to sign her name in the register. She was the daughter of the sawyer James Newell; it had been her mother Jane who had registered the death of Francis, attributing the cause as ‘Dentition’ after three days of convulsions.

One of several of that name, William Barnett, the child’s father, had been recorded in the 1851 Census as a gardener as West End. Otherwise listed as a labourer, he was the son of agricultural labourer James Barnett, a widower.

Charles Collins

The news that Charles Collins was dead had also begun to circulate that weekend. Not yet turned 60, he had been the master potter at the shop on the opposite side of the green to the smithy.

His funeral was to be held on Wednesday. The parish sexton, Thomas Attfield, would have been had time to brief the curate beforehand, alerting him to the prospect of many potters from the other side of Aldershot Heath attending the service. Thomas knew this well, having himself married into a family of Aldershot potters in 1830. His wife Rebecca was brother to Richard Chitty, their father John Chitty having been both a potter as well as the former parish clerk.

Charles’ niece would later travel to the market town of Farnham to register his passing and attribute his death to dropsy. The term then was used to describe the build up of fluids, such as in the leg or on the brain. No doctor had been called, as was typical for deaths in the village.

The niece was daughter of Charles’ brother William. Now aged 38, Mary had remained in the Collins family keeping house for her father and her uncle, as well as for all of her brothers before they left to marry. She had done so for over twenty-five years; her mother Sarah having died in February 1827. Her young sister, two year old Jane, was buried soon afterwards, in May 1827.

At first, Hannah, her younger sister by four years, had been a help but she had left to marry in 1838. The brothers, Henry and William, had both been in the family home in 1841, Henry, like his father and uncle, then recorded as a potter. In 1845, Henry married Elizabeth Hatt. She was the daughter of Daniel Hatt, recorded in the 1841 Census as a farmer in Bramshot Lane, Yateley. Henry had married well, resulting in them moving to Cove to operate his own pottery based at White Hall Farm.

Mary’s brother William had married the next year, in 1846, to Charlotte Hore when he was working as a potter in Farnborough; she was a servant there, the daughter of a farmer from Mapledurham by the Thames in Oxfordshire. William and his wife had moved back to Aldershot, taking on the other remaining pottery located by the Bee Hive Inn.

The 1851 Census had recognised Mary as a potter in her own right.

Sunday, 5th June 1853

Reverend Dennett had a baptism to perform at Matins. It would be the fifth he had to conduct in the first nine weeks of his tenure as curate, the fees he received being a welcome addition to his stipend.

John Matthews

Just how much Reverend Dennett would have been told about the parents of the infant John Matthews is less certain, nor of the extent to which the child’s parents had troubled family backgrounds.

The parents of the child to be baptised were Moses and Jane Matthews. The curate had not been present earlier in the year when his predecessor, Reverend Carey, had conducted the wedding of Moses Matthews and Jane Fludder; he had not, therefore, observed the bride walk up the aisle in a very expectant condition.

The curate had met others called Matthews four weeks previously in May when conducting the funeral of the infant Charles Young. The mother of that child had been Moses’ sister, Martha. Moses and his sister had shared tragedy in their childhood, both the death of their parents, their mother in 1843 and their father in the Farnham Workhouse in 1849, but also, before that, of a sister aged 13 in 1835 and the death of three brothers, variously aged 6 in 1836, 24 in 1839, 25 in 1842.

=> Matthews Family [to be added later]

Moses Matthews was a carpenter, as the curate made sure to note in the baptismal register. Before their marriage, Moses had been a lodger at the Bee Hive Inn. They were now renting a nearby cottage and garden from the owner, Mr Hall of Alton.

Jane, the mother of the child to be baptised, had been raised by her mother in her grandparents’ home. At age 9, she then became part of a blended family when her mother having married in December 1837. By 1841, the family were at the Kings Head, Frimley. Jane then had five half siblings: three from her mother’s marriage and two older children from her stepfather’s previous marriage. Jane had moved out by the time that family relocated to Fish Ponds in Farnborough in 1851. By then, Jane had become a mother herself, she and her infant daughter Lucy moving back to live in Aldershot with John Fludder, her uncle. Perhaps he had escorted her up the aisle on her wedding day and it was after him that the infant son being baptised was named.

The curate might have recalled meeting some members of the Fludder family before, when he had conducted his first wedding in the parish. That was of Jane’s Uncle William, a widower, who married Miss Carpenter at the start of April.

=> Fludder Family [to be added later]

Wednesday, 8th June 1853

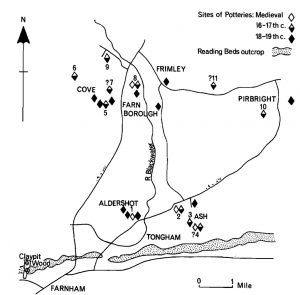

The funeral of Charles Collins was not the first funeral for Reverend James Dennett had to conduct in Aldershot but there would still be surprise at the sight of so many gathering. Not only was the Collins pottery a long-standing part of village life, the Aldershot potters were part of a much larger network of potters who for centuries had been producing what was known as the Borderware on either side of the Blackwater which ran between Northeast Hampshire and West Surrey.

=> Borderware

Competition from the likes of Wedgwood in Staffordshire and Doulton in London had diminished the national significance of Borderware pottery. Josiah Wedgwood and others had deployed better designs and more industrial forms of manufacture, long distance transport made easier by canals and then railways.

Ex: ‘A Preliminary Note on the Pottery Industry of the Hampshire-Surrey Borders’ by F W Holling, Surrey Archaeological Society, Vol 68, 1971. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000221

There were many connections forged over the years between the potters in Aldershot and those based in Ash, Cove, Farnborough, Frimley and as far away as Pirbright. It was also not unusual for young men from one family to work in another family’s pottery. There were also several intermarriages.

Potters would meet incidentally when collecting the white clay from Farnham Park, when foraging on the heath to collect turf for drying, but also for family occasions, those marriages having created additional bonds between them.

The heath all about the River Blackwater was important for turf which was cut according to a system that allowed the growth to come back within an eight-year period. They used wood to fire their kilns. Turbary rights to Aldershot Common were important.

Aldershot Potteries

Charles Collins had worked one of the only two active potteries in Aldershot with his brother William and William’s daughter Mary who had also been recorded as a potter by the 1851 Census.

Charles’ death signalled that end of an era was fast approaching for the craft of making pots from clay in Aldershot. Pottery and brick-making had provided employment in the village for many centuries. Even by 1841, there had been ten or more active potters. However, by 1851, there were half as many active potters, three being members of the Collins family. The others were the two journeyman potters, Richard Chitty and his son John.

William Collins and especially his daughter Mary would have wondered, once the word was around about the death of Charles, just how many they should expect at the wake after the funeral.

Whilst agriculture was the dominant activity in Aldershot, William would not have been the only one at Charles’ funeral with memories of what it was like when at least four potteries were active in the village.

The Collins Pottery

The main Collins pottery is marked as Plot 26 in the map drawn for the Tithe Apportionment Survey, shown at the foot of the left-hand panel below. It also features in the right panel, marked as Plot 357 in an extract of a map made around 1854.

Charles’ older brother William knew the story of how the pottery had come to be in their family.

William’s mother had been baptised Jane Cols in Aldershot in 1750, her parents James and Ann (Couls/Coules). William’s parents had married in 1767, his mother then 17.

William’s maternal grandmother, Ann, the daughter of John Baigent, inherited three copyhold properties in 1775. These included a “parcel of land commonly called the Park”, one acre in size, as well as a messuage, cottage or tenement, with outhouses buildings garden and orchard.

On her death, Ann’s will left part of her properties to her husband James; the parcel of land called the Park was left to John Collins of Aldershot, potter for his natural life and then to his son Henry Collins, William’s eldest brother.

When John Collins died in September 1800, William had been 15, Charles then aged only six. Their sister Elizabeth was eight.

It was then that the “messuage or tenement and potkiln and potshops with the land and appurtenances known as Park” passed to Henry. At age 32, he became head of the business, sharing the role as head of the family with his widowed mother.

The eldest sister Jane had already married ten years before, in 1790 to Robert Lloyd, a local farmer with a smallholding. She already had four of the nine children she would bear before 1815; the youngest, also called Robert, would latter marry Ann, the only daughter of the farmer Thomas Harding.

The second eldest brother John, also a potter, had also left home by 1800, marrying Mary Matthews. Her siblings were Mercy (who married William Wheeler, the cordwainer), Sarah (who married William Hone) and Stephen Matthews, the latter being the carpenter whose family suffered many tragedies. John and Mary moved away, settling in Wallington, in Fareham Hampshire, which is where they were in 1841. John died in July 1847, his widow surviving him, living on an annuity in 1851 and described in a later census as a potter’s widow.

Richard, another potter, was three years older than William. He did not marry, but was likely working elsewhere, later referred to in 1827 as ‘Richard, a potter from Frimley’.

Ann had been next to wed, in 1805, to a potter called John Smith, a potter in one of the four local potteries: three of their first children were baptised in Aldershot between 1809 and 1814. John and Ann Smith were in Mytchett in 1841, John active as a potter.

-

- Their eldest son Stephen was in Aldershot in 1841 as a potter, the 32-year old father of three young children, having married Henrietta Hennessy in August 1833 in the parish of Frimley. He was described there as ‘of this parish’ before returning to Aldershot. By 1851 Stephen was up by the wharf at Frimley as a potter, his two sons listed as potter and potter’s labourer.

-

- Their son Charles had also married in Frimley at age 22 in 1836. He was also a potter, in his own household in ‘Mytchett’ in 1841, likely working with his father. By 1851, John Smith having died, Ann and son Charles continued the business at Mytchett, sharing a household which included Charles’ son John, baptised in Frimley in December 1837.

William himself wed in July 1813, to Sarah Hamarton. The marriage took place in Worplesdon, a village to the east of Aldershot, between Pirbright and Guildford. Eliza, the first of their children was baptised in October 1813 at St Peter’s Church in Ash, William listed as a potter living at Westwood in the Parish Worplesdon. Sadly, the infant Eliza Collins died at 15 months old, buried at St Michael’s Church in Aldershot in December 1814. William and his family moved back to Aldershot, their daughter Mary was baptised there in May 1815; the next four of their children were also baptised at St Michael’s Church.

William’s wedding was preceded by what would appear to be a major family tragedy, the death of Elizabeth Collins, buried at St Michael’s Church on June 6th, 1813. Whilst no age was recorded, this was likely the sister Elizabeth who had been baptised in Aldershot as the daughter of John Collins in April 1792, therefore aged 21. She died of birthing complications, the baptism of Harriett, the daughter of Elizabeth Collins, listed as a servant, recorded at the same church on the same day, June 6th.

The widowed Jane Collins died four years later, in March 1817.

Not long after, it was Henry’s turn to marry, at age 49, to Elizabeth Marshall at St Peter’s Church, Ash in July 1817.

William could never forget the three deaths in 1927 which came in such quick succession. The first, in January 1827, was that of his brother Henry, then in February that of William’s wife Sarah, followed soon afterwards in May by the death of his daughter Jane, aged only four. The cause of deaths is not known but the suspicion must be that of a contagious disease, such as smallpox, typhus of cholera.

At the death of Henry, the property called Park passed to his widow Elizabeth, with debts owing to his brother “Richard Collins of Frimley, potter”, to whom Elizabeth mortgaged the property for £150.

William’s brother Richard therefore took charge of the business. Richard was aged 50, Charles then aged 32.

When Richard died unmarried in February 1836, it was not William but his younger brother Charles who took over the pottery . Just prior to that, in 1835, the widow Elizabeth Collins had sold the holding called Park, including the pottery, for £220 to Charles, by then aged 42, who promptly mortgaged it to John Allen Ward of Farnham.

William, however, was also a beneficiary of his brother Richard’s will, bequeathed other copyhold properties which Richard had bought from Samuel Andrews, a farmer and butcher from Farnham. One condition was that William had to pay £100 to his sister Ann, who had married the potter John Smith, and a further £20 to her daughter Mary. William promptly mortgaged the properties for £110 to John Allen Ward of Farnham, auctioneer.

The 1841 Census records that William and his brother Charles shared a household in the house by the pottery, together with William’s daughter Mary and sons Henry and William. HIs daughter Hannah had left to marry in 1838.

By 1851, the household comprised William, Charles and Mary. Now, with his daughter Mary, there were just the two working the Collins pottery.

The Smith Pottery

William’s son, also called William, was operating the other pottery in the village. It was owned by Mr Hall, the brewer from Alton.

The location of the pottery is labelled as such near the top and centre of the right hand panel, just above the Bee Hive Inn, also owned by Mr Hall. The pottery is at Plot 11 in the earlier map shown in left hand panel, the Bee Hive Inn in Plot 8. The pottery is also marked in Plot 254 in the right-hand panel.

Both enterprises had previously been owned by ‘Thomas Smith of Frimley’. He was referred to as such in 1841 so as to distinguish him from the locally born Thomas Smith who was the local farmer of 30 acres at Rock Place Farm at the West End of Aldershot.

-

- The pottery and other nearby properties were recorded in 1841 as occupied by ‘Charles Knight and others’, presumably under a lease from Smith who was otherwise absent. One of the buildings might have been for Knight’s own purpose as a shoemaker as there is no indication that he was a potter. The ‘others’ referred to were likely potters. (By 1851 Charles Knight had moved to Gravel Hill, Lower Bourne, Farnham.)

Thomas Smith, although a baker from Newtown, Frimley, had married Hester Robinson, the granddaughter of the Aldershot potter James May. At his death, May’s properties had been distributed in 1835 to his eighteen grandchildren which was when the pottery and the Bee Hive Inn became available to Thomas Smith. In addition to that left to his wife Hester, Thomas acquired additional properties by purchase from other beneficiaries of the will, both directly and by purchase of a mortgage. They would be put up for sale and bought by Henry Hall in 1850.

-

- It is unclear what relation, if any, that John Smith, the potter who had married Ann Collins in 1805, was to Thomas Smith of Frimley.

The Fedgeant Pottery

The third pottery in operation in 1841 had been located at the top of Drury Lane (Plot 6 in the left hand panel). This had once been owned and operated by the Chitty family, acquired by the potter George Faigent in 1789 from Ann Chitty, the widow of the potter John Chitty. It’s owner at the start of 1841 was George’s son, locally-born William Fedgeant, had died at the age of 59, buried in February. Jane, his widow, inherited the pottery as well as a cottage; she was recorded as living in Morland Cottages, in the household of her mother-in-law, Elizabeth Fedjent, aged 75.

-

- The surname had various spelling, including that of ‘Faggeant’ entered for a christening in the registers of St Michael’s Church as far back as January 1782.

With the death of her husband, and then deaths and departures of the young journeyman potters, the widow Jane ‘Faigent’ had become a laundress, listed as such by the 1851 Census. This suggests she had converted the pottery into a laundry: it certainly was not marked as a pottery on the map extract on the right hand panel.

When her mother-in-law passed away, Jane then shared a household with her daughter Elizabeth and her son-in-law and three small children. Elizabeth had married the baker Henry Elkins in 1845. He had been living close by in 1841, lodging in the house (Plot 21) of the ‘meal man’ George Baker.

The Gosden Pottery

That Henry Elkins was a baker by profession suggests another potential use for one of the other former potteries. This was likely the pottery which had belonged to Mr Gosden, the ‘house and premises’ on the corner of Drury Lane and the Street (Plot 15).

When William Gosden first arrived into the village, he was a former potter, born in Cove in 1783 to parents Lucy and George. He was baptised at St Peter’s Church in Farnborough where his uncle, also called William Gosden, had married to Ann, the daughter of the potter, Thomas Smith of Cove. (William Smith of Farnborough, Thomas’ son, who would later feature as a potter and farmer in the writings of George Sturt, was therefore Gosden’s younger cousin.)

Gosden was also described as a potter in a will in 1806, the same year he married in Farnborough to Mary Wheeler. Their first two daughters, Caroline and Lucy, had been baptised at St Peter’s Church in 1808 and 1810, although the family were in Aldershot by 1817 for the baptism of their daughter Harriet. William’s daughter Harriett would survive him, but her older sisters Caroline and Lucy died in their early twenties.

William’s wife Mary was only child and heir of John Wheeler from whom she inherited property in Aldershot when he died in 1815. Then, in 1818, William paid John Eggar £350 for a messuage (or tenement), a potshop and pot-kiln and a turfhouse and outhouses.

It is unclear when Gosden had ceased operating a pottery. His son George, who was born around 1820, and therefore a child when his father was acquiring farmland, never became a potter. By 1841, in addition to the former house and pottery (Plot 15), Gosden also owned two cottages and garden (Plot 13) and farm buildings and a yard (Plot 14) and about 20 acres of arable land, 11 acres of meadow and over an acre of land for hops. The 1841 Census recorded him as a shopkeeper and a farmer.

In 1828, William Gosden referred to as a potter, had paid Samuel Andrews, the butcher from Farnham, £850 for three parcels of land totalling 8 acres.

-

- Five years earlier, in 1823, Gosden had bought property from from John Chitty Stevens for £120, selling it on to William Tice for£145. Tice later bought two land parcels direct from John Chitty Stevens for £520.

The 1851 Census, conducted shortly before he died in May, recorded him as a farmer of 30 acres, his role as grocer by then performed by his son George. He had served as an Overseer for the parish on three occasions, 1836, 1841 and 1850.

William Gosden had also worked four acres of arable land in two fields called (H)Owlings and Bush Field (Plots 315 and 317) which were said to be owned by Daniel Bateman. He was the miller at Bourne Mill in Farnham.

By 1853, Daniel, his wife Harriett and their five young children had moved to Aldershot, occupying occupying the premises in Drury Lane as Bateman’s Corn & Forage Merchants. The Rate Book recording Daniel as the owner and occupier of 4 acres of land on which stood a house called Owlands.

In 1836, Daniel had married Harriett Collins, the daughter of the Elizabeth Collins who had died of birthing complications, the sister of the potters, Charles and William Collins. Harriett was heavily pregnant at the time of Charles’ funeral.

Journeyman Potters

The village had several other journeyman potters. They included some younger potters living in Morland Cottages in 1841. One was locally-born William Mullard, 25, living with his mother and his brother. William died in January 1848, his older brother Daniel was dead not long after, by October 1849. Their father Daniel had owned property in 1795 before selling to William Newnham, a gentleman; Daniel continued to operate the smithy by the village green.

Another potter in Morland Cottages was younger still, Robert Mason, newly married at age 20 to Ellen Fludder. His younger brother William, another potter, had fathered Matthew Matthews. They had all left Aldershot by 1851, Robert moving to the household of another potter, his uncle James Mason who had like his father been born in Farnborough. His father, also called Robert ‘of Cove’, had been a potter, recorded as having property in Aldershot, although not that of a pottery, as far back as 1782 when it formed part of a sale to Thomas Buddle, the future owner of the Halimote Manor estate.

By 1851, John and Richard Chitty were the only family of journeyman potters remaining in the village. Likely they had been working at Smith’s pottery when the Mullard brothers had been working at Fadjent’s pottery.

Thursday, 9th June 1853

The funeral took place for Rebecca Barnett, aged 33 and a mother of three. She had been baptised as Rebecca Chandler at St Peter’s Church, Ash in 1820. Both she and George Barnett were recorded in that parish register as resident in Ash when they married in May 1845. Rebecca was able to sign her name but not George. Elizabeth, their first child, was baptised at St Peter’s in January 1846 but the baptism of their second child in 1850 was in Aldershot.

Jane Bullen had been in attendance at her death was which attributed to ‘Consumption’, endured by Rebecca over a four month period.

Tuesday, 14th June 1853

The Camp at Chobham opened, the preparations for which, via the press, had proved successful in attracting the public’s attention. Special trains had being advertised for the expected crowds of visitors.

Some of those expected to take advantage of the crowds were less welcome. Instructions had been issued from the Home Office “to send a number of efficient constables immediately” without delay twenty men and two sergeants from the reserve force of each division”.

The day itself began with “no less than three thunder storms swept over the common, each accompanied with .. dense and heavy rain”, as reported the next day in the London Evening Standard and extensively elsewhere.

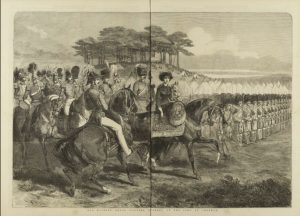

Most of the military activity was concerned with arrival, by train and by foot, and with each regiment pitching their tents. First the Household Brigade of Guards, then the 50th Regiment, followed by the Rifles and the 42nd Highlanders.

There was praise for the preparatory work of the Royal Engineers and Sappers, but also reports of the heavy and broken ground elsewhere causing cavalry horses to have severe falls, causing several to be put down.

Thursday, 16th June 1853

The Morning Chronicle carried a small snippet from its ‘own correspondent’ that news had been received “by submarine telegraph” from Vienna that the Russians had entered the Danubian Principalities and that “a panic had ensued”. The same article declared that another source had contradicted the report.

The same newspaper had a digest of a long article in the French newspaper, Le Pays, which contended that the “European Powers could not permit Russia to occupy the Moldovan and Wallachian provinces, because any such occupation, without a similar and simultaneous occupation by the Turks would be a direct violation of existing treaties”.

There was similar report in the London Evening Standard, noting the 1847 treaty of Delta-Liman, which also quoted the Berlin Temps, “a Government paper” in Prussia, as having stated that “the English Ambassador at Constantinople had been invested with extensive powers by the British Cabinet, with the restriction only that his lordship was not to consider the entrance of the Russian troops into the principalities as a declaration of war.”

The territories described above were one and the same. They had been a protectorate shared between the two parties at the end of the war in 1829 between Russia and Turkey. There had been various uprisings since against each associated with Greek Independence from Turkey and the move against Russian rule in 1848.

-

- Much of those territories now come within Romania.

Enclosure

What went unreported, and might have been only a source of rumour for most in the village, was that an application had been made on this day to enclose Aldershot Common.

The procedure under the Acts of ‘Inclosure’ was that application was made by persons interested in the land to be enclosed, representing at least one-third in value of the interests. The identity of the person or persons who had made the application is unclear.

An Assistant Commissioner was assigned to each application received, as part of the formalities of the enclosure process. A meeting was then called with fourteen days’ notice placed on the church door of the parish, and by advertisement. The latter likely meant a notice posted on the door of the Red Lion Inn.

Following his report, the Commissioners might then deposit a provisional order in the parish with notice of intent that the proposed enclosure would be put to the Secretary of State.

Application for enclosure had already been made for lands in the nearby tithings of Badshot and Runfold. By 1849, Binsted and Headley had already been subject to enclosure , of 990 and 1532 acres, respectively, followed by 108 acres at Bentley by 1851. The latter parish was the home of the Eggar family who would therefore have gained experience of both the process required and the benefits that could be derived.

Friday, 17th June 1853

The funeral done, Reverend Dennett wrote the name of Charles Chandler in the parish register. He recorded his age as 25 and that he was resident in Aldershot.

The cause of death is not known as none of that name and age was registered with the civil authorities, locally or anywhere else in England.

Nor was Charles Chandler resident in Aldershot in 1851. It is possible that this was the Charles Chandler who was baptised at St Peter’s Church in Ash in August 1831, as was his cousin Rebecca in March 1820; she had been buried at St Michael’s Church eight days previously, on Thursday, August 9th, recorded under her married name, Rebecca Barnett.

Saturday, 18th June 1853

The weekend newspapers carried reports of the Camp at Chobham which had opened on 14 June. The forces assembled for the first ‘field day’ were estimated at between 8,000 to 10,000 strong. The Duke of Cambridge was at the head of the Cavalry Brigade; Lord Seaton, the commandment for the Camp, led the Infantry Brigades. The newspapers reported details of the four hours given over to various manoeuvres and skirmishes.

The day, however, was mired, in both senses, first by an initial thunder storm and then, at intervals, by what were reported as “showers of pelting rain”. With Chobham Common described as a wild, extensive and heath-clad tract of land, poor drainage meant that parts soon turned to mud.

Even as the Camp at Chobham had begun, plans were being made for a better location for training camp in the following year. In a letter written on this day to Lord Seaton, Viscount Hardinge, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, disclosed an even more ambitious plan. Hardinge wanted a permanent camp of instruction capable of operating all year round, without the need to repeatedly hire land and request annual grants from Parliament.

Monday, 20th June 1853

The week in the village began with the wedding of Mary Ann Barnett, the daughter of William and Ann Barnett, to William Kircher, a labourer from Farnham on Monday the 20th. Reverend Dennett would have observed that the couple and the witnesses, the bride’s father and sister Caroline, had to make a mark when signing the marriage register.

William Kircher, now aged 22, was the younger of the two. He had been baptised in Farnham, at St Andrew’s Church, where Mary Ann, now aged 25, had been baptised two years earlier.

Mary Ann had been the eldest of five living with their parents in one of the cottages in West End in 1851. It was owned by Stephen Barnett. By 1853, her elder brother William, with a wife and child of his own, was occupying another of Stephen Barnett’s cottages.

It is not clear where the newly weds, William and Mary Ann, went on to set up home; William is not listed in the Aldershot Parish Rate Book for July 1853. In 1851, William had been living in his father’s household in Badshot, together with three brothers, all like himself listed as agricultural labourers, and his four younger sisters. Their father, Reuben, was a farmer of 17 acres. The likelihood would seem to be that William’s bride moved to Badshot.

Tuesday, 21st June 1853

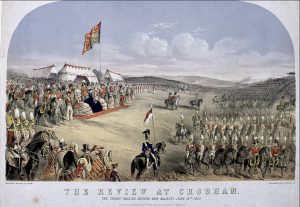

There was to be a royal review at Chobham. Visitors started to arrived to see the troops at drill, field operations and parades under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir John Colbourne, Baron Seaton. Queen Victoria herself paid a visit, first traveling by train to Staines and then by open carriage to the Camp.

The number of spectators who travelled to the Camp that day was estimated at 100,000, including those who had travelled by special excursion trains.

Review Chobham 21 June 1853 National Army Museum (Out of Copyright)

Wednesday, 22nd June 1853

Victoria was evidently impressed with what she saw, as shown in her letter from Buckingham Palace to her Uncle Leopold. She was, however, still preoccupied by worries about the Eastern Question.

Saturday, 25th June 1853

The Hampshire Chronicle carried report that, on the whole, the month’s weather had “been auspicious for the growing crops as could possibly be desired … The autumn sown Wheat has shot into ear, and that put in [during] the spring wears a more promising aspect than it did a fortnight ago.” The prospect for prices at market remained good, as the imports “expected from the Black Sea and Mediterranean have not come to hand”. There seemed to be a silver lining for domestic farmers in the mention made of “the uncertainty which exists as to how matters may terminate between Russia and Turkey”.

Most of the whole of page 3 of the Hampshire Chronicle was given over to an account of that earlier visit to Cobham by Queen Victoria. She had ridden upon a dark bay horse, to review her troops and then watch military manoeuvres and a mock battle.

However, had any villagers decided to visit the Camp at Chobham on that Saturday morning, they would have been met with rain descending in torrents. It was sufficient to prevent the start of operations at the Camp and to deter many spectators. The weather had cleared up by noon, and witnessed by Prince Albert and a party of distinguished foreign officers, the event was declared “the most brilliant field-day”.

Wednesday, 29th June 1853

By the following Wednesday, “owing to the fineness of the weather”, the number of visitors to the Chobham Camp increased. That was reported to have included both those of the aristocracy and “a very unusual number of fair[ground] equestrians upon the ground, who cantered in among the masses of troops or charged at the head of squadrons of cavalry”. The next day there was again to be a grand review attended by the Queen Victoria, her “illustrious visitors” taking luncheon at what was termed the Queen’s Pavilion.

Thursday, 30th June 1853

A letter is sent to Home Secretary Viscount Palmerston alerting him to the work of the Inclosure Commission and recommending that an enabling bill was put before Parliament to extend the life of the Tithe Commission which would otherwise expire in August.

=> July 1853