April 1853

The arrival of the young curate added to the sense of change in the village, providing an opportunity to see the place with fresh eyes. The talk amongst the farmers was of auctions and the weather, the arrival of Spring bringing renewed hope for improvement in agricultural activity.

Nationally, the focus was on the upcoming budget from the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, William Ewart Gladstone. With continuing concerns about the tensions in Turkey between Russia and France, there was also keen interest in the return to Constantinople of Britain’s Ambassador, the recently ennobled Viscount Stratford de Redcliffe.

Saturday, 2nd April 1853

As for the weather, it was wet.

“Towards afternoon of yesterday the weather

… suddenly changed its mind and gave us another spice of its quality.

About six o’clock the rain came down in torrents and

continued to fall without intermission till six o’clock this morning.

The weekend edition of the Morning Advertiser went on to declare,

“.. the month of March,

in place of coming in like a lion and going out like a lamb,

came in like a bear and has gone out like a tiger.”

Regardless, one advertisement in the Hampshire Chronicle that Saturday was sure to have grabbed the attention of farmers in the village. Auctioneers Trimmer and Hewett would be putting 53 acres of hop and arable under the hammer. Lands in neighbouring Runfold, Tongham Moor and Seale were to be sold in eleven lots at the Bush Hotel in Farnham, at three o’clock a week on Tuesday.

The back page of the Hampshire Chronicle carried a snippet of news which might have passed unnoticed, having little apparent significance at the time. Mentioning the extensive encampment of troops on the race ground at Chatham, it noted that decisions were being taken on the selection of locations for Summer camps of instruction, with grounds near Sandhurst and Ascot Heath being considered.

Captain Newcome

Another entry in the Hampshire Chronicle likely to have been read with possible curiosity was on behalf of the ‘Hants County Hospital’ in Winchester. Beneath news that the physician for the week would be Dr Hitchcock, there was the announcement of a new subscriber, none other than “Captain Newcome, Aldershot Manor, near Farnham”. He was listed as having taken out subscription to the value of £1- 1s.

As recorded in the 1851 Census, he was ‘late Captain’ of the 47th Infantry, his rank still used as his formal title. Captain George Newcome had not long been in the village, although, with effect from March 25th, he now served alongside Charles Barron as a churchwarden. He had taken over from Mr Barron to chair the Vestry, as though signalling a more significant change.

The entry in the 1851 Census stated that Captain Newcome owned 63 acres, employing two labourers and a boy, in what was the fourth largest land holding in the parish, in a house which was second only in terms of grandeur to that of Charles Barron Esq. .

Newcome had bought the Manor House estate only seven years before, in 1846. He was not, however, as might have been implied in snippet in the Hampshire Chronicle, the owner of ‘Aldershot Manor’. When John Eggar had sold what the Rate Book had then referred as the ‘Great House’ to Matthew Bridges in 1842, the ‘Aldershot Manor Halimote’ had passed to his brother Samuel Eggar. And, in any event, there was surprise in store about what that meant.

With Newcome on Census Night were his wife Harriet, five servants and three visitors. All had been born outside the parish. The visitors included Charles Short, together with his wife and daughter, recorded as a West India Merchant and also a former Captain. Charles Short had served in the Coldstream Guards. He had probably been present at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, as had Harriot’s brother, Charles Andrew Girardot, also of the Coldstream Guards. In fact, when Charles Short had been promoted to Ensign ‘without purchase’ in 1814, he had replaced Harriot’s brother who had been promoted, also without purchase, to the rank of Captain. These were military men promoted on the basis of merit; Girardot was destined later to reach the rank of Colonel.

In contrast, George Newcome’s military career of 15 years and 8 months was ‘by purchase’ and ‘by exchange’; his advance could be considered to have been well crafted. He began as an Ensign with the 14th Regiment of Foot, ‘exchanging’ within a month to join the more illustrious 88th Foot, later to be stationed in the Ionian Islands. As Lieutenant in the 88th, at the death of his father, he become a Captain the 47th Regiment ‘by Exchange’, paying half pay to another, and briefly serving at that rank in the West Indies in 1841.

His appointment and status as an army captain would have assisted George Newcome to marry well, as he did in May 1844 to Harriot Sophia Girardot in Little Bookham, Surrey, the ceremony conducted by her brother, the Reverend John Girardot. They came from a French Huguenot family once based in Derbyshire where their father had been High Sheriff. John Charles Girardot had moved to the Little Manor House, Little Bookham by 1841, then aged 70, with his unmarried daughter Louisa. He died in July 1845, a year after Harriot’s marriage.

George and Harriot Newcome moved to Aldershot, into what was known as the Manor House in 1847. George Newcome might already have known something of the area as two of his sisters had earlier married into the Mangles family who were settled close by at Poyle House, Tongham and in Woodbridge, near Guildford.

=> More about the Newcome family, and who really owned Manor House.

=> More about the ‘Mangles Brothers’ in later chapters.

The Second Panic

The same newspaper reported the story about a deputation sent to Paris with document signed by 4,000 merchants, bankers and other commercial men from London:

The object of this remarkable document is to remove the impression,

alleged to be existing in the minds of the French people, that the people of England entertain an unfriendly feeling towards them.

The Emperor Louis Napoleon had addressed the deputation in English, professing his desire for peace. He wished to counter the contrary impression in the editorials of the British press.

Richard Cobden M.P. was later to describe the years leading up to 1853 as ‘The Second Panic’, triggered in December 1851 by the coup d’etat led by Louis Napoleon. Subsequently re-elected as President of the French Republic, the nephew of Bonaparte then declared himself Emperor in December 1852.

Many former military and naval officers had taken to writing pamphlets and letters to the national press, as well with articles in the two weekly periodicals, the Naval and Military Gazette and the United Services Gazette. An alarm was sounded about French intentions. After four years of reduction in military and naval expenditure, a rapid growth in the prosperity of the country had provided the Treasury with a surplus funds.

Partly in response to what Cobden termed ‘invasion-panic’ amongst the public in 1852, much amplified by the press, the Government had introduced a Local Militia Bill. This proposed the enrolment over three years: at first the plan was for 70,000 men, then 100,000 and finally the total would rise to about 120,00 in the third year. In the event, the passing of an amendment to that Bill was the trigger for the fall of the Whig Government from which Viscount Palmerston had been excluded two months earlier.

-

- Palmerston had previously been the long-running role as Foreign Secretary, popular in the Commons and the country for his patriotic stance. However, he was seen to have exceeded his authority by providing approval for the coup d’etat by Louis Napoleon of December 1851, consulting neither his Prime Minister nor his Queen. He had been obliged to resign.

A Minority Tory Government came to power, introducing a new Militia Bill. Gaining the support of Viscount Palmerston, who vigorously championed the measure, the bill was passed, granting the Government authority to raise 80,000 men. When that Minority Government fell at the end of 1852, a Coalition Cabinet was formed headed by Lord Aberdeen. That included Viscount Palmerston at the Home Office with direct responsibility for the Militia.

As Cobden was to write,

“Such was the state of feeling in the Spring of 1853.

The nation had grown rich and prosperous with a rapidity beyond precedent … it seemed only a question upon whom we should expend our exuberant forces – whether on France or some other enemy”

Items from the United Services Gazette found wider readership through their repeat in other newspapers. One such was that stated in the London Evening Standard about how Viscount Hardinge, Commander-in-Chief was advancing his reforms of the military. He had expressed the view that “the efficiency of a corps was materially deteriorated by being cut up into detachments”. He believed that towns would now have to find their own police, “the British Army spared a duty that did not properly belong to it”. The same report noted that the 2nd Battalion of the Life Guards would encamp on Bagshot Heath early in May.

It was later reported that Hardinge had made a new rule that he would not appoint any candidate to a commission unless he had been on the list for twelve months, “however powerful may be the interest used in his behalf”.

Viscount Hardinge had been encountering resistance to the reforms he had been pursuing since his appointment as Commander-in-Chief of the Army last September. Prominent amongst the ‘Old Guard’ was Lt General Sir George Brown, appointed Staff Officer and Adjutant-General in 1850. He had been passed over for the post of C-in-C at the death of the Duke. Brown was loyal to the former regimental system associated with Wellington and resentful of Hardinge’s “restless propensity towards innovation”.

Hardinge was not unarmed as a reformer, however, nor was he alone in proposing change. He himself has also been close to Wellington, and indeed was the Duke’s nominee as his successor. Moreover, he brought a breadth of experience to the post. He shared his plans with the long-time proponent of army reform, General John Colborne (Baron Seaton). Neither were from wealthy families, they had both advanced with successful military command and had experience as in colonial administrator, Hardinge in India and Seaton in Canada and the Ionian Islands. Hardinge had also been both the Master of the Ordnance and a former Secretary at the War Office. Despite not sharing much of their politics, he had the support of the men in the Cabinet, including the current Secretary of War, and he was well connected with the Palace.

Viscount Hardinge had been in the news for other reasons. The Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal had reported on April 1st that “The London correspondent of the Liverpool Standard states ‘beyond all probability of doubt or cavil’ that Lady Peel was about to be married to no less distinguished a stateman and warrior than the present Commander-in-chief, Viscount Hardinge.”

Although the date was long known as April Fool’s Day, the story was syndicated across the country by other regional newspapers as though it were true. It eventually prompted reportage to the contrary:

A stupid paragraph … has been going the round of the newspapers.

Lord Hardinge is a married man, his wife being the sister of the present Marquis of Londonderry.

The absurdity of the report … is manifest to all who are aware that

… Lady Emily Hardinge .. is alive and well and residing with Lord Hardinge, who is a most devoted and attached husband.

A Village Wedding

The state of the weather was regarded as of more importance by several others in the village that Saturday. That was especially so for the Fludder family who gathered once more at the parish church. Their ardent wish after Friday’s downpour was for the chance of sunshine to match the occasion of the wedding of William Fludder to Miss Jane Carpenter.

For the groom’s sister, Esther Hughes, the year was only three months in and already there had been three family gatherings at the Church of St Michael. First, there was a funeral in January of her young nephew Frederick, then another in February for her mother-in-law, Mary Hughes. Fortunately, those sad occasions were followed in March by a much happier event, that of the marriage of young Jane, Esther’s niece. And now there was to be a wedding of Esther’s older brother William. Aged 57, he had been a widower for over twenty years. His first wife Mary had died in 1832, only two years after they were wed.

A year or so before this second marriage, William had jointly occupied the family’s cottage in North Lane with his brother John who was also widowed. William’s forthcoming marriage had prompted the two brothers to subdivide the family home in North Lane into two cottages: the Rateable Value of £4 then assessed as £2 each. The household beforehand had included John’s two teenage sons and their niece Jane Fludder with her infant daughter. Jane had recently moved out having herself married only two weeks before, to Moses Matthews.

Caroline Hone, the blacksmith’s wife, would very likely be another at the wedding. She was second cousin to the bride; she and Jane Carpenter were of a similar age. Jane’s mother had been first cousin to Caroline’s father Thomas Williams and to her uncle James Williams the Chelsea Pensioner, all baptised in Farnham.

Had the weather held, the bride would have processed up the steady incline of Red Lion Lane and then along the avenue of tall elm trees in Church Road, the initial pink blossom turned bright green as a sure sign of Spring. Although unmarried, Jane was not herself, however, in such an early bloom of youth. She was 35. She had been the sole companion to her widowed mother for most of those years.

Seemingly, Jane was an only child, made an orphan when aged only four. Her father had been a schoolmaster, buried in 1822 at the same church at which she was now to be married.

-

-

- The link between Jane’s father as schoolmaster and Caroline’s selection as village schoolmistress is suggestive. However, John Carpenter had died in 1822 when Caroline would have been only four years old, the same age as Jane.

-

The bride’s parents had married there, many years before in 1809. Her mother, then Mary Williams, had to make her mark in the marriage register. Now it was Jane, like her father, who was capable of signing her name in the register and it was her husband who had to make his mark, even though he was a shoemaker.

Jane Carpenter and her widowed mother had shared a household two doors up from the Red Lion Inn, her mother, listed in 1851 as in receipt of parish relief. Passing away in February 1852, Mrs Carpenter had been aged 77. Only then it seems had Miss Jane been free to marry the man twenty years her senior.

The curiosity amongst the congregation that day was prompted by more than the advanced ages of the bride and groom. The clergyman officiating looked so young in comparison. He was unlike his predecessor in very many ways, not only his youth but some might have discerned an ‘ampshire accent beneath the mannered speech of a minister.

More eyes were on the young man when he conducted Sunday Matins the next day.

Sunday, 3rd April 1853

James Dennett’s time in the cities of Southampton and Cathedral city of Winchester would have provided him with a rich experience, exposing him to Baptists, Independents and various type of Wesleyan as well as those of the Roman Catholic faith. There were also soldiers garrisoned in both cities.

Aldershot would have seemed a quiet and suitable place for Dennett to have his first parochial appointment, a rural parish of almost universal Anglicanism. Like his predecessor, he might have wondered whether his life now would be full of baptisms, weddings and funerals. Fortunately, there would be no burials at which to officiate during his first month of tenure.

The christenings that morning were not the first he had conducted at the Church of St Michael. Members of the congregation might have recalled that he had officiated at Epiphany Sunday at the start of the year. It was then that he had baptised the son of Francis Henning, the superintendent of the District School. Some might also have brought to mind that the infant had died not long afterwards.

This time, however, James Dennett was able to record his new status, writing “Perp. Curate for Aldershot” under his signature in the parish register for the baptisms of three daughters.

Ann Gravett

Ann was the daughter of Leah and William Gravett of Copse Lodge. William worked as the Keeper on the Aldershot Park estate for Charles Barron Esq.

Leah had two other children from a previous marriage in Ewhurst to David Ede, an agricultural labourer. She had been widowed in 1844. William Gravett was then working nearby at Highedgar Farm, also as an agricultural labourer. Leah and William had married in Ewhurst in February 1847, their first son George buried later that year at only eight weeks old. The move to Aldershot, with William’s appointment as a keeper, represented a fresh start, William now 37, Leah aged 33. Baby Ann’s elder brother had been baptised at St Michael’s Church some eighteen months before.

Mary Porter

Mary was the next child to be admitted into the Church through baptism. Her parents, Stephen and Eliza Porter, had married at St Michael’s Church in 1839. They were living in a rented cottage owned by Mrs Tice which was close by Copse Lodge.

Stephen had also been baptised in Aldershot at St Michael’s Church in 1812, although his family were from Runfold where Stephen had been born. His parents now lived in Badshot. Despite both small hamlets being geographically in the Parish of Farnham, across the county boundary in Surrey, on the other side of the Pea Bridge at the Blackwater, St Michael’s Church in Aldershot was much closer than Farnham’s parish church of St Andrew’s.

-

- This was before the Church of St John was completed in 1844 at what became the Ecclesiastical District of Hale, the family home of Bishop Sumner.

The infant Mary was one of five young children in the family, all recorded in the baptismal register at Aldershot; William, the eldest, had been baptised in November 1839. On each occasion, Stephen was listed as a labourer, although the 1851 Census recorded him as a carter. He was locally famous for winning the prize as champion ploughman at last year’s Alton Fair, entered then as working for Mr Richard Allden.

Mary’s mother Eliza was also from a family of agricultural labourers. She had been baptised at St Andrew’s Church in Farnham in 1817; she was from Hoghatch where her parents, James and Mary Raggett, were in 1841 before they too had later moved to Badshot.

Amelia Vear

The third infant baptised that Sunday was not the child of an agricultural worker. Amelia’s father was instead the landlord of the Row Barge Inn up on the Turnpike Road, near the wharf for the Basingstoke Canal. Amelia was one of five daughters born to Sarah and of Clewer Vear. The 1851 Census recorded Clewer Vear as both a publican landlord and a bricklayer. Having two occupations was quite normal for inn keepers. It was certainly true for the landlords of the two public houses within the village, the Beehive and the Red Lion.

As its name suggests, the Row Barge served the needs of those associated with the canal that cut across Aldershot Heath, first those who built it and then those who used it, especially the potters in the area whose products were sent up to London.

Given its location, few from the village would have ventured out to the Row Barge without special cause. Just when Clewer Vear had became its landlord is unclear. The birth of his older daughter Julia was registered near Bracknell at Easthampstead in late 1848; she was not baptised in Aldershot. However, the toddler Jane Vear had been baptised at St Michael’s Church in 1851.

-

- Older members of the congregation might have recalled that the Row Barge Inn had earlier been held by the Shurville family, from 1831 to 1844, first by John Shurville, then Jane and finally Thomas. The 1841 Census records Thomas Shurville and his wife Jane having three infant children. The household included seven others, some of whom might have been paying guests. Thomas Shurville had also been farming 14 acres owned by Mary Lambourn just north of the Canal. By 1851 the Shurville family had moved to Fish Pond, Farnborough, Thomas becoming a farmer of 28 acres employing one live-in labourer.

Recent Deaths in Village

Thomas Harding died in October 1850. In January of that year, he and Clewer John Vear of the Row Barge had been tried and found guilty of keeping hours beyond the legal hour of 11 o’clock. Both were given penalty at the Odiham Petty Sessions of 3s. 6d and costs of 11s. 6d, each paying the sum immediately.

Thomas Harding was then the farmer at Shearing Farm on North Lane. The supposition is that he might either have kept a beer house at his own premises or have been the landlord at the Red Lion Inn before George Faulkner who had taken up the position by 1851.

The death of Harding is associated with a number of other subsequent changes in the village. His daughter Ann had married Robert Lloyd in 1838. Robert was listed as an agricultural labourer in 1841, but by 1851 he described himself to the Census as a farmer of 10 acres; it is unclear whether this was Shearing Farm, the enterprise previously farmed by his father-in-law, or land through which Lloyd’s Lane would run.

Thomas Harding’s wife, also called Ann, had stayed on in the farmstead, her household in 1851 including not only her locally born servant, Richard Barnett, but, supplementing the annuity upon which she depended, she also had a lodger named James Williams.

Aged 67, James Williams was listed in the Census as a Chelsea Pensioner, born in Farnham. Like the blacksmith’s father, James Hone, Williams was also a veteran of Waterloo, his regiment, 23rd Foot, being present at the battle in June 1815.

-

- James Williams was balloted in Farnham at age 19 to join the Reserve of the 57th Regiment of Foot. This was in 1803 when war had broken out against the French once more. A general call for recruitment led to the 57th Foot, also known as the West Middlesex, to raise a 2nd battalion. He served an initial seven years of balloted service in 1810, before then transferring to the 23rd Regiment of Foot. His service record notes a pension for service in the 23rd Foot from the year 1810 in addition to that for his balloted service.

James Williams had also died in recent year, just after the 1851 Census was taken. The cause was certified as cystitis, George Turner, of Farnham, another Chelsea Pensioner of similar age, in attendance. James’ death on 14 May 1851 was registered the next day; he was buried two days later in Aldershot at St Michael’s on 17th May 1851.

Ten years before, James Williams has been as a lodger on North Lane with the Callingham family, recorded in the 1841 Census as was Caroline Williams, the village schoolmistress lodging with the Wheeler family. It seems very likely that James was Caroline’s uncle, the brother of her father Thomas Williams.

-

- There were, however, two of the name James William baptised in Farnham in 1784, one in May and the other in September, to two different sets of parents. One set of parents was Isaiah and Rachel Williams, James being the younger brother of Thomas. The other James Williams baptised in Farnham in 1784 might have been the one recorded by the 1841 Census as living in the Epsom workhouse, aged 60 and from Surrey.

That James Williams was her uncle adds plausible context for two life events for Caroline. First, when she arrived to be to the village schoolmistress, she would have had the reassurance of a relative in Aldershot. She would then lodge in a household of the daughter of a cordwainer, another term for a shoemaker as was Caroline’s father. Second, Caroline’s later marriage in 1843 to Henry Hone, the son of soldier, might also not have been such a coincidence: her future father-in-law was a veteran of Waterloo, as was her uncle; both were born in Farnham and likely had some form of prior connection which had brought Caroline and Henry together.

Monday, 4th April 1853

Had the curate decided to visit the Bishop at his palace, he may well have encountered a large gathering of men at Farnham Park. This being the first Monday of April, it was the annual ‘Clay Audit’ at which potters from all across the locality. They came to settle their account for the fine white clay which they had used to produce top quality Borderware pottery, sometimes known as ‘Surrey Whiteware’.

In earlier times, the green glaze used during the 16th and 17th Century had given rise to the term Tudor Green. However, much of the pottery supplied as London’s redwares had also come from the potteries operating along the Blackwater using other types of clay.

The full extent of the contribution made by the potters of Aldershot would not yet be plain to the young curate as by 1853 there were only two working potteries in the village; both were operated by members of the Collins family.

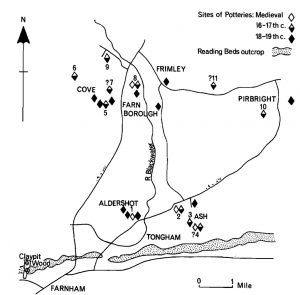

Pottery kilns had existed to the north-east of Farnham for many centuries, as shown in a sketch map based on archaeological findings at Farnborough, Cove, Frimley and Pirbright as well as Aldershot and Ash.

Ex: ‘A Preliminary Note on the Pottery Industry of the Hampshire-Surrey Borders’ by F W Holling, Surrey Archaeological Society, Vol 68, 1971. https://doi.org/10.5284/1000221

Farnham Park and Tongham were the acknowledged source of the fine white clay used in pottery sold in London and abroad as far as Jamestown in the American colonies, its green glaze giving rise to the term Tudor Green. However, much of the pottery supplied as London’s redwares, coming from other types of clay, also came from the local Borderware potteries.

By 1853, competition from the more industrial manufacturing, typified by Wedgwood in Staffordshire and Doulton in London, had diminished the national significance of Borderware pottery. Regardless, several active potters remained. They would meet incidentally when collecting the white clay from Farnham Park, when foraging on the heath to collect turf for drying, but also for family occasions, marriages creating additional bonds between them.

The heath was important for turf which was cut according to a system that allowed the growth to come back within an eight-year period. They used wood to fire their kilns. They all relied on turbary rights on Aldershot Common.

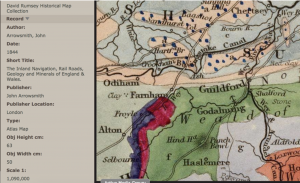

The variety of soil type in the area is displayed in a map by John Arrowsmith published in 1844. The key in the map makes distinction between the clay for brick (shown as blue/grey) and potter’s clay (pink).

Wednesday, 6th April 1853

Reverend James Dennett had much to learn about his new parish. Stood at the top of Church Hill, James would have recognised some aspects of the outlook, especially the view north onto the heathland. The farms were similarly scattered all across both of the Hampshire parishes. Dennett’s home parish also had clay to support the making of bricks, used in large part in the city and port of Southampton.

There were, however, some obvious differences from the edge of the New Forest where James’ father, mother and sister still lived. There, the call of the gulls from the estuary at Bailey’s Hard, also called Buckley’s Hard, was the dominant sound. The parish of Beaulieu was also twice the size, extending over more than 9000 acres, nearly 8000 acres of which were heath and woodlands adjoining the forest. The population was also larger than Aldershot, with a count of 1,177 at the 1851 Census.

Moreover, the land, the tithes and the patronage of the living as curate were all in the hands of a single grandee, the manor having passed to Walter Montagu Douglas, who as 5th Duke of Buccleuch and 7th Duke of Queensberry held vast estates in England as well as Scotland. He had been personal body guard to Victoria at her coronation and had served in Peel’s Government in the 1840s. The Duke maintained a hunting lodge in the grounds of the old Beaulieu Abbey.

The Vestry

The young curate’s immediate challenge this day was the meeting of the Vestry, the principal locus of formal authority for the village. This was opportunity to discover how power and control was structured in the absence of a dominant aristocrat.

James Dennett might have wondered what his role in this parish would be, confronted with the seniority of these men around the table at his first meeting of the Vestry. Looking around the room, all the others assembled were at least twice his age.

As part of his training in Winchester, Dennett would have learnt that the incumbent of the parish had the right ex officio to be present and to take part in every meeting of the Vestry. More than that, he also had the right to take the chair and preside over its deliberations. The young Reverend James Dennett, however, would not be its chairman at this meeting.

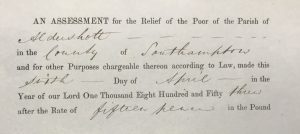

Despite earlier minutes of meetings of the Vestry revealing that the Dennett’s predecessor had sometimes taken the chair, that role was now exercised by the laity. Captain George Newcome was chairman that evening, the sole item of business, as subsequently recorded in the minutes, being the setting of the Rate for the Relief of the Poor at 15d in the Pound.

Captain Newcome of the Manor House, who would likely have led the introductions, was fifty years old, a man with experience of military command in the West Indies. Charles Barron of Aldershot Place was in his early sixties, a seasoned businessman and land proprietor from London.

The two Overseers for the year were Thomas Deacon Esq, also from London, and Mr James Elstone, the enterprising farmer and employer of thirty men. They were both aged about fifty. So too was Richard Allden, another yeoman farmer and large-scale employer in the parish, whom the curate would have encountered at the time of his appointment. Together with Reuben Attfield, another in his fifties, these were the leading members of the ruling elite.

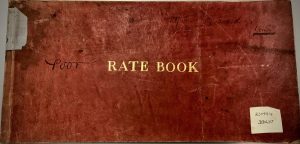

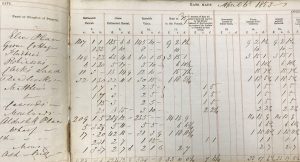

Reuben Attfield now occupied the paid position of Assistant Overseer. He kept the minutes and other paperwork for the Vestry, including the entries made in the Overseers’ Receipt & Payment Book and the Poor Rate Book, both of which were present at meetings of the Vestry.

The administrative year having ended on Lady Day, 25 March, the Overseers’ Receipt & Payment Book had been closed off and duly signed off and dated by the two outgoing Overseers. It would be submitted for auditing in June.

The collection of the Poor Law rates and other taxes was another of Reuben Attfield’s responsibilities, shared with Henry Twynam, a tenant farmer aged 48.

The Poor Rate Book on the table contained a list of the names and addresses of all the ratepayers and would be able to tell the curate much about his new parish.

Messrs Attfield and Twynam had been prompt in the collection of the rate. That was duly signed off that day by Reuben Attfield and the two incoming Overseers, Elstone and Deacon.

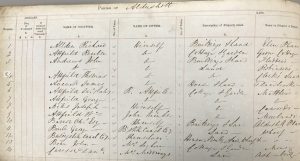

On the left hand of the page listed the owner of each of the 216 rateable properties, the occupier and a brief description of the rated property and its name.

Each right-hand page listed the area of the property, measured in whole and part acres, as well as the assessed Rateable Value and an account of the rates payable and collected. Also indicated were instances where the owner rather than the occupier paid the rates, an indicator of tied housing.

Inspection of the entries would have made plain to the curate the extent to which the wealthy were well represented amongst the members of the Vestry. But first, the Rate Book had to be taken to Winchester for approval and sign-off by two Justices of the Peace.

An eager James Dennett would also have been keen to examine the Overseers Book in order to learn more about the practice of the Vestry towards poor law relief. That too would have to wait.

Sunday, 10th April 1853

Reverend Dennett had no baptisms at which to officiate at Matins. Instead, he was called upon to read out the ‘Form of Thanksgiving’ for the health of the Queen and her infant prince. This had been commanded at all churches and chapels across England and Wales by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Buckingham Palace had issued an announcement on the previous Thursday:

“The Queen was safely delivered of a Prince at ten minutes

past one o’clock this afternoon.

Her Majesty and the infant Prince are well.”

Just when news of the event would have first reached Aldershot is unclear, but likely it was well before the details in syndicated report from the London Gazette Extraordinary appeared in the Hampshire Chronicle at the end of the week.

Named Leopold, after Queen Victoria’s uncle, the King of the Belgians, the child was fourth in line of succession, the eighth to survive birth during the Queen’s first 13 years of marriage.

-

- The delivery of Prince Leopold included the novel and controversial use of Chloroform which might have formed a topic for village discussion. He had inherited haemophilia from his mother and at the age of 30 he would predecease her.

Tuesday, 12th April 1853

Aldershot’s Poor Law Rate Book for April 1853 was presented in Winchester. A total sum of £ 131- 1s. 6 ½d had been raised in Aldershot for poor relief and highway maintenance.

A bill had been introduced in the House of Lords earlier in the year on compulsory vaccination against Smallpox. It had passed its second reading and was at the Committee stage on that Tuesday. The bill required compulsion. Mothers were to be advised of their responsibility when registering births and vaccination required of any person entering the country.

Quoting the Report compiled by the London Epidemiological Society, Lord Lyttleton had explained that the incidence of deaths from small pox was as high as 100,000 in the ten years to 1760 but had fallen since 1780 down to 16,000 in the most recent ten years.

The argument made was that vaccination had been saving lives but also that compulsory vaccinations were even more effective for this highly contagious and nasty virus. Lyttleton remarked that during the forty-eight years that had elapsed since the opening of the Royal Military Asylum (School) at Chelsea, where vaccination was enforced, there was not a single death from small pox after vaccination amongst 31,705 admissions, and only four from second attacks of unvaccinated persons.

Earl Shaftsbury stated that the effect of the compulsory system, when established in other countries, had been almost to exterminate the disease there. It was compulsory in Prussia, with small-pox accounting for 7.5 per 1,000 deaths, and in Berlin where it was as low as 5.5; in Copenhagen it was nearly so, with 6.75. Where vaccination was permissive, such as in London and Glasgow, the rates were very much higher, at 16 and 36 per 1,000 deaths, respectively.

Saturday, 16th April 1853

Readers of the Hampshire Chronicle were rewarded with an account of the course of lectures which had been given by Professor Michael Faraday at the Royal Institution on “Static Electricity”. Various experiments were demonstrated, including the “excitement of electricity that takes place whilst combing or brushing the hair when dry” and the “charge to a small Leyden jar by which gunpowder was fired.”

Tuesday, 19th April 1853

As the month progressed there were newspaper reports about preparations for the formation an extensive encampment for summer camps of instruction, later to be referred to as the Great Encampment. The Morning Post carried a story about its location; according to reports, regiments were to march to Chobham Common by late May or early June.

The big story in the daily newspapers, however, was of William Gladstone’s first Budget. It was viewed as a triumph. Whilst railing against Income Tax, arguing that it should be abolished, he proposed to continue it for a further seven years, after which it would cease.

-

- Gladstone proposed “to re-enact it for two years, from April 1853 to April 1855, at the rate of 7d. in the £; from April 1855, to enact it for two more years at 6d. in the £; and then for three years more … from April 1857, at 5d. Under this proposal, on 5 April 1860, the income-tax will by law expire.”

The coverage of this direct tax was also to increase, lowering the threshold for Income Tax to £100, at a reduced rate of 5p in the £. The tax had previously applied only to incomes above £150. The logic was to include those who were educated and had the vote, but to exclude those who laboured without that responsibility.

The Chancellor also extended the legacy (succession) tax to real property, raising an additional £2m. That and his use of Income Tax enabled relief to the burden of hundreds of indirect taxes. The highlight was the abolition of tax on soap which cost the exchequer over £1m and the reduction in the duty on tea and various foodstuffs. The duty on newspaper advertisements was also reduced and stamp duty on receipts was cut to a flat 1d.

Much of this, although perhaps not the extension of the Income Tax coverage, would have found favour in the village, as it was across the country. Also noted was the reduction in the tax levied on horses, dogs and male servants.

Saturday, 23rd April 1853

William Gladstone’s Budget was reported in great detail in the Hampshire Chronicle on the following Saturday.

The Hampshire Telegraph did much the same, describing it as a “hybrid budget – a coalition budget – a budget of compromise, but, on the whole a useful budget.” It declared the imposition of a legacy duty on real property to be a simple act of justice and concluded that “With [the exception of failure to repeal the advertisement tax] the new budget … if not perfect, .. is an immeasurable improvement on that of Disraeli.”

Benjamin Disraeli had been the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the previous Government which had fallen when his Budget had been defeated.

Opinion amongst the farmers in the village would have been divided as, unlike the Budget unsuccessfully proposed by Disraeli in 1852, Gladstone’s Budget did not include the hoped for 50% reduction in the duties on malt and hops .

Saturday, 30th April 1853

Confirmation that the Camp would be at Chobham were included in the weekly summary of reports in the Hampshire Chronicle. A matter of interest to some in the village but not thought to be one of major significance. That confirmation in writing might have put to rest any concerns raised had any villager observed Viscount Hardinge riding across Aldershot Heath as he had also done in March just past.

Neither the Chronicle nor the Telegraph made much of the increases in the estimated expenditure for the Army and Commissariat. Part of that for the latter was retrospective (£200,000) but most was prospective (£700,000). There was also an alert that a further sum (£23,000) would need to be put aside for the plans “my right hon. Friend [the] Secretary for the Home Department” has for the Militia. This was none other than Viscount Palmerston.

As erstwhile Foreign Secretary, he had asserted British interests abroad through a balance of power. That had been based upon distrust of the so-called ‘Holy Alliance’ of Russia, Prussia and Austria and an alliance with the former foe of France. This remained the stance of Lord Clarendon, now the Foreign Secretary, both with respect to the maintenance of the integrity of the Turkish Empire against the press of Austria on Montenegro and also a wish that Russia did not impinge upon other Turkish possessions.

Lord Clarendon had begun his career as an attaché to the British embassy at the Russian Court.

The Hampshire Chronicle reported in its edition of April 30th the view expressed by Lord Clarendon that he saw no reason to expect any disturbance to the peace of Europe, nor any interruption of the unanimity which prevailed between the Great Powers on the Turkish question. This formed part of his reply to a question asked in the House of Lords on April 25th, basing his answer on intelligence received from Ambassador Viscount Stratford, from “a telegraphic despatch was also received yesterday, which stated that up to the 14th inst. all was quiet at Constantinople.”

Lord Clarendon had summed up the Government’s challenge in reconciling the competing pressures from Russia and France upon Turkey in a single, rather long and convoluted sentence:

“The Turkish Government, having made to the French Government certain concessions in respect of the Holy Shrines which appeared to be inconsistent with previous concessions made to Russia,

“the Emperor of Russia, knowing the great interest felt by the population in the East in respect to the Greek shrines, and regarding his own position in reference to that Church, determined upon sending Prince Menschikoff upon a special message in order to arrange this matter, and to place the question of the Holy Shrines upon a permanent footing.”

Communications with its Ambassador to Constantinople over the coming months would be subject to a delay of around 10 days, each way. Much would depend, therefore, upon the ability and judgement of Viscount Stratford and his statements to the Turkish Government and other parties at the Porte.

=> Story continues as May 1853